Migrant and Refugee Rights in Morocco: Between Strategic and Exceptional Solutions

Citation: Zaanoun, Abderrafie (2023) ‘Migrant and Refugee Rights in Morocco: Between Strategic and Exceptional Solutions’, Rowaq Arabi 28 (2), pp. 31-53, DOI: 10.53833/UDJW1968

Abstract

This paper aims to trace whether and to what extent the human rights dimension is incorporated into migration and asylum policies in Morocco and to observe the impact of these policies on the conditions of migrants and refugees in the country, as reflected in reports issued by government authorities and international organisations. Relying primarily on a descriptive analytical approach, it seeks to determine the degree to which programmes implemented from 2013 to 2023 fulfil human rights entitlements and to analyse the gap between the normative human rights framework and practice. The paper finds that ever-shifting migration policies have undermined the basic rights of migrants and refugees. The lack of an integrated strategy has fostered an ad-hoc approach to a vital issue which requires holistic, participatory planning that meets minimum human rights requirements. The study shows that the sustainable realisation of migrants’ rights cannot be achieved with piecemeal modifications of migration policies, but rather through the vigorous pursuit of equal rights for citizens and non-nationals, in line with Morocco’s constitution and its international obligations, while putting in place the necessary guarantees to balance internal and external needs in the management of migration and asylum affairs.

Introduction

Morocco’s handling of migration and asylum issues has evolved in line with the changing nature and magnitude of migrant flows and as its own position within the regional migration matrix has shifted from that of a source country for migrants to a country of transit and settlement, within the framework of ‘alternatives’ that it has begun testing in cooperation with the European Union. New migration pathways entail both risks and opportunities, especially considering Morocco’s growing role in international migration governance—it hosted the Fourth Ministerial Conference of the Euro-African Dialogue on Migration and Development (the Rabat Process), contributed to the development of the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration (GCM), and is home to the African Migration Observatory—and the difficult task of balancing various interests with humanitarian considerations in controlling migration flows towards Europe.

Although Morocco adopted a national strategy for migration and asylum in 2014 and subsequently initiated several programmes to expand migrants’ and refugees’ access to some public services, it has not wholly abandoned the use of exceptional means to settle long-standing problems. This is due to both internal and external factors, such as the securitisation of migration policies and fraught position of migration issues in partnership and cooperation agreements between Morocco and its European and African partners. Considerable diplomatic stakes are at issue as well, as Morocco seeks to consolidate the rights of Moroccans living abroad, soften European positions on the Western Sahara, and persuade European countries to adopt the Moroccan proposal for a peaceful resolution of the conflict.[1] To take just one example, Spanish-Moroccan cooperation on migration faltered when Spain received the leader of the Polisario Front; in response, Morocco began easing its efforts to control the flow of irregular migrants and some 10,000 migrants made it to Spanish territory in May 2021, further fuelling tensions.[2] The crisis was brought to an end with the ‘rewriting’ of the political consensus undergirding the migration partnership: on 18 March 2022 Spain recognised the validity of Morocco’s proposal for autonomy, while Morocco in turn expressed its willingness to redouble efforts to control migration.[3]

Much research on migration and asylum policies in Morocco looks at the push factors that fuel displacement and the impact of geopolitical shifts on migrants’ conditions while disregarding how this impacts the nature of responses and their effectiveness in improving the human rights situation of migrants transiting or temporarily residing in the country. Although some studies try to tease out the overlapping Moroccan and European interests in managing migration and highlight the effects of voluntary return and reintegration programmes on migrants’ conditions,[4] they largely confine themselves to Moroccan expatriates, focusing on secondary issues in measuring the impact of national programmes and partnership projects. Moreover, insofar as they are limited to an evaluation of the development of resources and projects while disregarding the human rights dimension and without linking it to migration policies and public policy as a whole, they lack critical depth. This paper will therefore seek to address the human rights impacts of migration policies and examine the nature of government responses to migrants who settle in or transit through Morocco.

This study explores the following question: What approaches has Morocco adopted to manage migration and asylum affairs and how has its model of migration governance impacted the human rights situation of migrants and refugees? This central question generates several secondary questions: In what areas is a rights-based approach most apparent and what are the consequences of Morocco’s vacillating pursuit of a strategic-oriented course and an exceptional course when resolving migrants’ status? Is Moroccan migration policy a restrictive or open policy? Where might it be possible to develop and reorient national migration and asylum policy to meet the actual needs of migrants and refugees in light of new challenges?

The study posits that fluctuations in the human rights situation of migrants and refugees in Morocco are tied to the nature of measures taken by the state: the more these measures are based on strategic planning and a participatory approach, the better they fulfil human rights requirements. Conversely, the more exceptional they are, the less sustainable and the less responsive they are to the needs of migrants and refugees.[5]

To best explore the central research issue and answer the secondary questions it raises, the study relies on descriptive analysis to extrapolate the frame of reference and analyse national and international reports on the rights and freedoms of migrants and refugees. It uses a more historical approach to understand the context of the evolution of Morocco’s engagement with and treatment of foreigners transiting through its territory, and relies on a quantitative approach to inventory and sort data relevant to the status of migrants and refugees in Morocco.

The paper is divided into five sections. It begins by laying out a theoretical framework through which to understand the overlapping external and internal dimensions of the governance of human movements before turning to an examination of the position of human rights in the development of migration and asylum policies in Morocco in part two. In part three, I attempt to evaluate the accomplishment of government interventions, while part four highlights some of the problems that affect the human rights situation of migrants and refugees. The paper ends with a section dedicated to exploring ways to enable a human rights-oriented approach to managing migration and asylum affairs.

Theoretical Framework

The literature on migration is full of various theories that explain the dynamics fuelling migratory movements and the ways in which migrant networks and migration management systems take shape. These include the push-pull theory, which posits that migrant flows are determined by factors that spur migrants to leave their homelands (civil wars, ethnic discrimination, the deterioration of standards of living) coupled with variables that incentivise movement to specific countries (political stability, the quality of social services, easy access to jobs). Donald Bogue elaborated a theoretical model to explain the trajectory of migration, holding that migration is a multi-stage process, starting with migrants leaving their country of origin and ending when they reach the destination country after passing through transit countries.

The dual labour market theory draws on this same theoretical background but looks at cross-border human movements from a holistic perspective, arguing that migration is not the result of push factors in the source countries, but rather pull factors in the receiving countries, in particular the increased demand for foreign labour.[6] It describes the labour market in Western economies as two-tiered, consisting of a primary sector that provides good jobs with attractive incentives for highly skilled migrants and secondary sectors that provide low-wage jobs for temporary migrant workers.[7] This theory asserts that the discriminatory treatment of foreign workers is not merely an accidental manifestation of the two-tiered market economy, but is rather bound to the essence of modern capitalist economic systems, which prefer irregular migrants because they are easy to control and employ at low wages with minimal obligations. In turn, this fosters the formation of ‘black markets’ for the smuggling and employment of irregular migrants by transnational human trafficking networks.[8]

Several theories have adopted a political economy perspective on migration to understand migrant labour in industrialised countries, whose policies have long functioned to entrench temporary migration through the ‘importation’ of migrants absent recognition of their fundamental rights while regulating legal migration to ensure a stream of skilled workers from specific source countries for their national economies.[9] This has led some scholars to posit that migration flows are linked to the international division of labour in the capitalist system, which requires a regular supply of workers who respond to its needs.[10] European countries continue to offer financial and technical assistance to incentivise countries that export the most migrants to codify avenues of migration in a way that ensures that the most skilled migrants are able to immigrate.[11] At the same time, the ‘Europeanisation’ of the issue of migration has tended to entrench a security approach to irregular migration through various arrangements aimed at deporting undesirable migrants and refugees.[12]

In this context, several theories have emerged to explain the roots and outgrowths of the security perspective on migration. Securitisation theory, for example, as developed by Copenhagen School theorists Barry Buzan and Ole Weaver, asserts that turning social issues into a matter of security justifies exceptional government means to address them. Drawing on this theory, Didier Bigo holds that European countries consider migration to be a major security problem that threatens their national identity, leading them to use special means to address it,[13] tightening border controls and dealing firmly with all attempts to penetrate them. In turn, this entails the criminalisation of various aspects of irregular migration and functions to enhance the powers of the security services to deal with the problem of migration, which is no longer seen as an economic phenomenon but rather a security issue to be analysed by a security professional.[14] In the same vein, pioneers of the Paris School were interested in analysing the practices of security professionals assigned to border control. Jef Huysmans saw the influx of irregular migrants as a major challenge to the political, social, and cultural security of Europe.[15]

Other theories have attempted to explain the continuity of irregular migration, the way it is constantly renewed, and how efforts to absorb irregular migrants lead to more migration. Migration network theory, for example, analyses the factors governing shaping migration, which, in addition to the authorities in both the source and destination countries, include the networks of middlemen and human traffickers who control the routes and outlets for the movement of migrants and refugees.[16] The spatial theory of migration focuses on cost and attractiveness as determinants of migrants’ identification of areas for transit and destination, analysing the variables that function to privilege certain migration routes between source and host countries, such as mileage, costs, and time.[17]

In contrast, still other theories emphasise the reciprocal relationship between migration and development. For example, migration system theory stresses that improving the legal and economic situation of migrants has a positive impact on the opportunities for economic and social development in countries of origin.[18] The analytical depth of this theory remains limited, however, since it confines itself to the analysis of small units absent an exploration of the historical and political origins of irregular migration and the nature of the relationship between the countries that control migration flows. Transit countries, for example, seek to take advantage of their position to play a strategic role in regulating the volume of migrant flows, thus ensuring political and economic gains for themselves from exporting and receiving countries. In this context, migrants and refugees are reduced to mere numbers in a geostrategic game that has long-term human rights repercussions that are difficult to control. Even the assistance that receiving countries give to source countries only mitigates symptoms, being dedicated to voluntary return, reintegration, and resettlement programmes without fundamentally addressing the political and developmental roots of the phenomenon. The obsession with security means that most of the funds earmarked for integrating migrants go to tightening border control, and integration policies quickly devolve into policies of exclusion, isolating migrants pending deportation or allowing them transit based on certain arrangements with receiving countries.

Accordingly, most international experiences in managing migratory flows have seesawed between two approaches with very different premises and stakes: a human rights approach that links migration with the right to movement and the right to development, and a security approach that prioritises state sovereignty and border control in dealing with migration. Although both source and receiving countries of African migration gesture towards humanitarian entitlements in migration and asylum arrangements, security considerations have determined the various measures taken, which has given rise to double standards in the positions of the parties regulating regional migration, especially the European Union. On the level of discourse, Europe adopts human rights when formulating migration and asylum policies, but this rhetorical stance has not been adequately reflected on the ground. European solutions aimed at absorbing irregular migration flows have not been matched by integrated development programmes in the countries of origin, to say nothing of the double standards in evidence in processes for the regularisation of migrants’ status and respect for the right of asylum.[19]

Despite the remarkable progress in regional migration governance thanks to a growing willingness to ratify international conventions and the increasing involvement of international organisations, the reality is that international standards for the treatment of undocumented migrants are only poorly applied given that international economic policies persist unchanged.[20] This has implications for migration policies in countries of origin and transit, which are ultimately nothing more than a local iteration of the European model. In turn, attempts to enshrine a human rights approach to managing migration and asylum are turned into a mere facade for the codification of security-based solutions dictated by Europe. Indeed, Europe has persistently prioritised stricter border control measures in various migration cooperation and partnership agreements in order to ensure that migration programmes in transit countries are tailored to European needs, even at the expense of these countries’ domestic interests and international obligations.

The Rights Dimension in Evolving Migration and Asylum Policies in Morocco

Early migration and asylum policies in Morocco were variable and temporary in nature because they consisted of ad hoc, piecemeal measures. There was accordingly little if any consideration given to human rights in most past programmes. When some rights dimension was in evidence, it was a political gesture that aspired to ‘humanise’ security measures against migrants. In the absence of a fixed, national frame of reference, the Moroccan position remained dependent on shifts on the European side, which sought to ‘export’ its migration policies through various exclusionary solutions[21] like readmission, voluntary return, and deportation. As a result, migrants’ enjoyment of fundamental rights and freedoms was similarly variable. Some periods witnessed a more prominent human rights approach to addressing migration problems: measures were taken to protect vulnerable migrants, and border police were given more training on the humanitarian treatment of irregular migrants. At other times, the security approach was dominant, demonstrated by an uptick in apprehensions and arrests, more frequent discriminatory and abusive practices, and limited compliance with humanitarian standards when dismantling migrant camps.[22]

Although Morocco was one of the first Arab countries to ratify the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (the Migrant Workers Convention) in 1993, due to its reservations on Article 92, the ratifying law was not published in the Official Gazette until August 2011,[23] pursuant to the provision in the 2011 constitution that gave ratified international treaties supremacy over national legislation. The human rights dynamic in the second half of the 1990s, set in motion with the beginning of the democratic transition and the transitional justice process, did not have positive repercussions for the situation of documented migrants.

With the beginning of the new millennium, anxieties about security came to dominate migration management amid an international climate conducive to linking counterterrorism and irregular migration, especially after 11 September 2001, with adverse consequences for the rights of migrants and refugees.[24] This anxiety underpinned the drafting of the 2003 law on the entry and residence of aliens and irregular migration in 2003,[25] precluding the effective consolidation of the civil and social rights of migrants and refugees, who were now required to obtain residency bonds as a condition for access to public services.

The new challenges of managing cross-border human movement dictated that discrete, sectoral measures had to be situated within a uniform strategy to ensure harmony between internal and external questions, based both on an international framework, which recommends developing practical measures to mitigate violations against migrants and refugees, and on the 2011 constitution, which stipulated in Article 30 that non-nationals shall enjoy the same fundamental freedoms as Moroccan citizens. Hence, in July 2013, the National Human Rights Council (CNDH), together with the Inter-ministerial Unit on Human Rights and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), prepared a guidance document that stressed the need to establish a legislative and institutional framework that could accommodate the new dynamics of migration.[26] To the same end, and in the same year, the CNDH published a report in which it called on the authorities to adopt an effective public policy on migration that would uphold rights and would be based on international cooperation in the movement of persons.[27] The report constituted a reference point to frame the authorities’ efforts to articulate a new perspective that would respond to the actual needs of migrants and refugees and accommodate new international trends in the rights-oriented management of migration affairs,[28] first and foremost the recommendations of the Global Forum on Migration and Development, which urged member states to fully integrate migration issues into national policies by 2014.

Based on these reports, on 18 December 2014, the government approved the National Strategy for Migration and Asylum, making Morocco the first country in the Middle East and North Africa region to draft a strategic plan on migration and asylum.[29] The date was not without symbolic significance, coinciding with both International Migrants Day and Morocco’s ratification of the Migrant Workers Convention. The strategy set forth twenty-seven goals and eighty-one projects, adopting a comprehensive approach to managing migrant flows while respecting human rights,[30] thus avoiding discrimination and inhumane treatment and ensuring the same access to basic services for citizens and non-nationals.

The strategy provided that national legislation be brought in line with international standards. International Labour Organisation Convention No. 143 on Migration in Abusive Conditions was thus ratified in 2016, followed by ILO Convention No. 97 on Migrant Workers, and actions were taken to begin the ratification procedure for ILO Convention No. 118 of 1962 on the equal treatment of citizens and non-citizens in social security. All of these efforts came as the international treaty framework regulating the rights of migrants was solidifying amid new obligations that stressed responsible, sustainable migration management. The Sustainable Development Agenda (2015–2030), for example, called on signatory states to improve the legal and institutional system of migration in order to reduce inequality and facilitate the movement of people in a regular, safe, responsible manner.[31]

To modernise the legal and institutional regulation of migration, a committee was formed under the supervision of the Inter-ministerial Unit on Human Rights. As a result of the committee’s work, legislation was enacted to curb clandestine irregular migration, such as Law 27.14 of 2016 on human trafficking, which introduced substantive and procedural amendments to the Penal Code to criminalise various aspects of human trafficking, including the smuggling of migrants.[32] An executive decree issued in 2018 to clarify the modalities of implementing the law set forth the functions and composition of the national committee tasked with coordinating action to combat human trafficking, within the framework of completing the procedures for Morocco’s accession to the Global Action against Trafficking in Persons and the Smuggling of Migrants.[33]

With regard for a framework to govern asylum, the CNDH called for the development of a policy to integrate refugees and their families in the fields of housing, health, education, training, and employment. It also urged guarantees of respect for the principle of non-refoulement coupled with the development of a national legal and institutional framework to regulate refugee status and asylum criteria.[34] The CNDH recommendations formed the basis for an asylum law drafted in March 2014, which was to be placed on the Cabinet agenda on 16 December 2015, before being withdrawn pending the inclusion of new amendments and further consultations with various stakeholders, starting with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). A new version of the law was drafted in 2017 and named a Cabinet priority in September 2018, but was withdrawn again in order to reach a consensus on the optimal procedure for processing asylum applications and mechanisms to resolve the legal status of refugees.

Although a review of the draft law on asylum was completed in February 2019, the law has not yet seen the light of day.[35] As a result, hundreds of asylum seekers have been forced to navigate the complex procedures in effect at the UNHCR and the Office for Refugees and Stateless Persons.[36] Operations at the latter office in particular are erratic. Where once its role was merely to approve the files of refugees recognised by the UNHCR, it is now tasked with assisting asylum seekers in determining refugee status, and steps have not been taken to enable it to function optimally in its new role. Accordingly, there is a pressing need to facilitate asylum procedures and unify the operative regulatory framework, given the multiplicity of agencies involved, including the government sectors in charge of the interior, foreign affairs, justice, and human rights.[37] The human costs of the deteriorating conditions of asylum seekers prompted the state to initiate extraordinary regularisation processes to enable them to access basic services.

The Rights of Migrants and Refugees: Strategic Horizons Versus Ad Hoc Responses

By 2013, the backlog of migrants without legal status made it necessary to put in place urgent measures to improve their situation. The organisation of these exceptional processes heralded a fundamental shift.[38] The government created a national committee tasked with regularising the status of migrants and integrating them on 17 September 2013. On 6 June 2014, it established a specialised committee to track regularisation files and reconsider previously denied applications under the supervision of the CNDH. It became apparent that maximum flexibility was needed to accept the applications of as many African migrants as possible given the political sensitivity of migration in Morocco’s relations with African states.

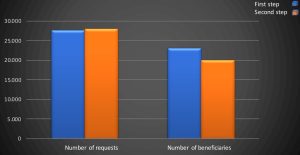

The exceptional status resolution process went through two stages, the first in 2014–2015 and the second starting on 15 December 2016 and lasting one year. During that time regional offices were opened to receive regularisation applications, while regional and state governors supervised the committees established to monitor local operations and, in conjunction with institutional actors like the CNDH and some civic bodies, to organise awareness campaigns to encourage migrants to submit applications. As a result, the administrative status of most undocumented migrants was regularised, as shown Figure 1.

Figure 1

Outcome of the Extraordinary Regularisation of the Status of Irregular Migrants

Source: compiled by the author based on data from the government sector on migration affairs

According to official data, eighty-five per cent of applicants were approved in the first stage of the exceptional status resolution process[39]; this approval rate stayed roughly the same after the national committee ruled on appeals.[40] All told, the status of some 50,000 undocumented migrants was resolved from 2014 to 2018; of them, 43,000 applications were accepted[41] based on criteria that gave priority to migrants with employment contracts who had lived in Morocco for at least five years. Applications were accepted as well based on other criteria set forth in the joint periodical issued by the minister of interior and the minister in charge of migration on 16 December 2013, which made accommodations for non-nationals with chronic diseases, or those married to Moroccans or legally residing in Morocco.

As a result of the exceptional regularisation process, more than 45,000 migrants were given temporary residence cards valid for three years by the General Directorate of National Security.[42] In addition, a preliminary integration plan was initiated to give migrants and their families access to basic rights,[43] such as their children’s right to education. Pursuant to the plan, 3,227 pupils were registered in various levels of education and 304 people were enrolled in continuing education programmes in the 2020/21 academic year. Migrants were similarly given access to health services, including free medical assistance services and treatment campaigns such as the National Maternal and Child Health Programme and the National Immunisation Programme. The number of beneficiaries of health care facilities increased from 23,758 in 2019 to more than 30,000 in 2020 with the start of the implementation of the strategic plan for health and migration 2021–2025,[44] which entailed multiple projects to facilitate vulnerable groups’ access to health services. Thanks to these efforts, the IOM held up Morocco as a model for the gradual integration of migrants with low or no income in the health system.[45]

Migrants who benefited from regularisation were also given enhanced access to the labour market. They can avail themselves of the services of the National Agency to Promote Employment and Skills and have been integrated into state-funded employment programmes, and the process of applying for work visas based on employment contracts was simplified. As a result of measures taken from late 2015 to early 2021, this category of migrants has concluded 1,261 employment contracts, while more than 1,500 people have taken advantage of vocational integration programmes.[46] The social and humanitarian assistance programme has also provided clothing, food, medicine, and legal advice to some 2,000 migrants.[47] Other advances have brought Morocco international acclaim thanks to its structural projects for the integration and reintegration of migrants.[48]

Regarding refugee status, with transit to Europe subject to ever-stricter procedures, Morocco has become a country of residence for a large number of migrants, which spurred an increase in asylum claims. Morocco thus reconsidered its previously stringent asylum procedures, initiating a serious of exceptional settlements to clear the backlog of applications. On 17 September 2013, a committee was established under the chairmanship of the minister of foreign affairs and cooperation to regularise the status of refugees recognised by the UNHCR.

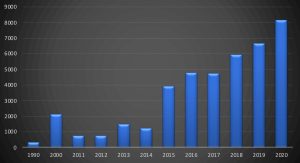

The first phase of the regularisation process, from September and November 2013, involved multiple inquiries and hearings conducted by the UNHCR and the Office for Refugees and Stateless Persons, which resulted in the approval of 577 asylum claims.[49] The first batch of asylum and residence cards began to be delivered to refugees and their families on 24 December 2013. The second phase of the process began on 23 January 2014 and is slated to continue until the enactment of the asylum law.[50] All told, 5,618 people were recognised as refugees between September 2013 and December 2018.[51] While the preliminary outcomes of the extraordinary regularisation process reflects a dynamic, creative approach to the recognition of the right of asylum in Morocco—the number of recognised refugees increased from 1,458 in 2014 to 8,161 in 2020—the persistence of impromptu solutions and the lack of an integrated legal framework governing the treatment of refugees limits the effectiveness and sustainability of Morocco’s asylum policy.

Figure 2

The Evolution of Refugee Numbers in Morocco

Source: compiled by the author based on data from the World Bank[52] and the UNHCR.[53]

Recent data show an improvement in the rate of refugee approvals in Morocco. In 2021, the country hosted 8,300 recognised refugees compared to 6,642 in late 2019, for an increase of about twenty per cent. The same period has seen a surge in asylum seekers as well, from 4,400 at the beginning of 2020 to 5,400 at year’s end and 5,700 by mid-2021. Some fifty-five per cent of them come from Syria, twenty-five per cent from sub-Saharan African countries, and the rest from elsewhere in the Middle East, especially Iraq, Palestine, and Yemen.[54] These figures, however, do not accurately reflect the size and status of the refugee community in Morocco given that it is constantly changing. Every year, Morocco recognises hundreds of refugees, but at the same time, other refugees leave the country, voluntarily returning to their countries of origin or departing for other countries.[55] The impact of deportations must also be considered,[56] as well as the fact that some refugees do not submit regularisation applications due to fear of deportation or because they are waiting for the chance to move to Europe.

The regularisation of refugees’ administrative status has enabled them to access medical and educational services, facilitated their integration into the labour market, and allowed them to receive legal and humanitarian assistance. These and other measures were lauded by the UNHCR,[57] which played an important role in assisting government authorities in following up on the registration of asylum seekers and strengthening national capacities to cope with refugees. This partnership continues to evolve. The UNHCR signed a framework agreement with the CNDH on 14 April 2021 to strengthen the national system for the protection of refugees and shape public policies that are more responsive to their needs and rights.

Limited Human Rights Impact: Indicators and Issues

Morocco has long received international acclaim for its systematic turn from the security-oriented management and implementation of migration policies to a human rights-based approach.[58] However, attempts to cement the human rights dimension in migration and asylum policies does not mean that the gains achieved for migrants and refugees can be banked on, for new constraints call into question the durability of this progress. Moreover, the temporary nature of ad hoc solutions undermines the sustainable empowerment of migrants’ rights, with old problems quickly resurfacing once exceptional processes are concluded.[59] At the same time, the ranks of undocumented migrants continued to swell after 2018 because the Moroccan authorities failed to initiate a new round of regularisations that would give them access to basic services like their counterparts covered by the 2014 and 2016 processes. By 2023, there were nearly 50,000 migrants residing illegally in Morocco,[60] and they are not included in official statistics.[61] The same is true for refugees: about half of them are in constant need of protection while 7,398 asylum seekers from forty-eight countries have not yet been able to obtain or renew a refugee card.[62]

Despite the gains achieved, then, key problems persist that limit the access of migrants and refugees to some basic services. The lack of civil status documents and school certificates deprives migrants’ children of the right to education.[63] The right to health coverage is still constrained by the requirement to show identification documents in order to access medical services, and security anxieties further impact migrants’ enjoyment of this vital right. Fear of arrest or the confiscation of identity documents in the event of the non-payment of medical bills leads many to avoid health facilities. The refusal of the latter to hand over birth certificates also deprives the new-borns of migrants of other rights such as vaccination, care, and education, not to mention the right to identity.[64] The same considerations apply to the right to work. The difficulty of obtaining decent work leaves migrants vulnerable to exploitative labour conditions and forces them into low-wage jobs in construction, domestic work, and the informal economy, which denies them of all forms of social protection and health insurance.[65]

The complex conditions that must be navigated to take advantage of available services has given rise to multiple forms of inequality between non-national residents in Morocco.[66] Different categories of migrants face discrimination in status based on their geographical origins. This has been especially visible amid the emergence of a new pattern of migration by citizens of some European countries who do not require a visa to enter Morocco. If many of them settle their legal status with the local and consular authorities, others continue to work in the country without being subject to any legal framework.[67] Signs of discrimination against African migrants—virtually the only group of people to whom the term ‘migrant’ is applied[68]—have also begun to appear, coupled with a disparity in rights between refugees recognised by UNHCR and those officially recognised by the Moroccan authorities. In addition, national migration and asylum policies are built for citizens of the Global South while migrants from the Global North are described as expatriates or foreign citizens.[69]

In regard to gender, some affirmative action measures were approved for female migrants without legal status, especially in the second phase of the exceptional regularisation process, where applications were processed based on extremely flexible criteria. As a result, the status of all migrant women who submitted applications to the committee supervised by the CNDH was regularised.[70] Some measures have also made it possible to reduce cases of gender-based violence and the exploitation of female victims of human trafficking, while supporting migrant women’s access to social and humanitarian assistance programmes. Additionally, a set of programmes was put in place—for example, the EU-funded Tamkin Program, carried out in partnership between the Ministry of Health and non-governmental organisations—to strengthen the capacities of health professionals to better understand the special needs of migrant women.[71] Despite these efforts, however, gender-based disparities in the enjoyment of rights and access to services persist, as women are more vulnerable to violations and exploitation. Some thirty-eight per cent of migrant women are involved in domestic work where conditions are precarious and the relationship between employers and migrant women is poorly defined and regulated.[72] Some of these problems spring from the failure to adopt a clear gender-sensitive approach to migration policies and legislation, as well as the limited guarantees of legal protection for migrant women facing various forms of discrimination and inequality and the anaemic safeguards afforded to some groups at risk of marginalisation, sexual exploitation, and human trafficking.

Regardless of how many people have been covered by integration and reintegration policies, certain measures have perpetuated the exclusion of non-nationals whose legal status has been regularised. There have been numerous arrests of migrants who leave their city of residence, including non-border areas.[73] The movement of non-nationals without residence cards is severely restricted; they are subject to special surveillance and leaving their assigned areas requires a police pass. Other indicators demonstrate in concrete terms the limitations of the integration mechanisms stemming from the national strategy and the exceptional regularisation entitlements. Indeed, the latter have at times served as a justification for intensifying security campaigns against irregular migrants. In 2018, for example some 5,000 people were arrested, some of them later concentrated in remote areas in the south while others were dispatched to areas on the country’s eastern and southern borders,[74] after which large numbers of migrants were deported. According to official figures, six per cent of foreigners who entered the country illegally were forcibly returned to their countries of origin.[75] The CNDH has also documented many cases of non-nationals being arrested and involuntarily transferred to other cities or deported without regard for existing legal procedures—operations that entailed discrimination, arbitrary arrest, and the disproportionate use of force.[76] Moreover, new waves of migrants have been concentrated in ‘ghettos’ in the form of makeshift camp settlements, where they live a life of displacement, deprivation, and exploitation by gangs of smugglers and human traffickers.[77]

These indicators are particularly worrying because they are associated with structural factors, meaning they are liable to worsen regardless of strategies put in place to curb them. A chief stumbling block is the failure to fully conform with the international normative framework. Morocco has still not completed all the procedures to ratify ILO Convention No. 143 on Migrant Workers after its approval by parliament in 2016,[78] and some deportation measures for refugees contravene the minimum guarantees set forth in the Geneva Convention of 1951 and its implementing protocol. Furthermore, Morocco is not a signatory to other conventions that are vital to effectively consolidate the rights of migrants with legal status, among them ILO Convention No. 157 on the Maintenance of Social Security Rights and ILO Convention No. 87 on Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise.

An equally important factor is the instability of the regulatory framework. The successive interruptions of the work of the Office for Refugees and Stateless Persons negatively affected the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which had adverse impacts on the status of refugees. Similarly, the suspension of the work of the joint committee tasked with receiving asylum claims from December 2017 to December 2018 had implications for the management of the second phase of the exceptional regularisation process.[79] The same is true for the management of migration: poor coordination among relevant actors had adverse repercussions for the human rights situation of migrants, while the unclear distribution of powers and prerogatives between central agencies and local authorities impacted responses to the needs of migrants.

Prospects for Advancing the Rights of Migrants and Refugees amid Contemporary Challenges

Although in recent years Morocco has tried to distance itself from Europe’s security-oriented approach to migrant flows, it continues to come under pressure to conform to the European model, and in particular to accept various options for the settlement and integration of irregular migrants outside of the European continent. Other challenges are mounting as well that will affect Morocco’s position, first and foremost demographic explosions and the multi-faceted implications they have for African states in migration belts. Meanwhile, Europe is projected to lose some forty-nine million people of working age by 2050.[80] Morocco is thus likely to face a new influx of African migrants making their way to Europe, which means that the demographic transition is a crucial consideration in migration management.[81] Climate change, too, will exacerbate instability. According to the International Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, about two million people in sub-Saharan Africa were forced to leave their homelands in 2019 due to climate-related disasters.[82] According to the World Bank, if the necessary measures are not taken, the number of climate migrants from sub-Saharan Africa will reach eighty-six million by 2050.[83]

In addition to these ‘natural’ factors, tumultuous economic and security conditions in the countries of the Sahel and North Africa make the western Mediterranean a preferred route for African migrants crossing to Europe. Morocco will therefore confront far heavier migration flows, especially as Europe is increasingly closing its borders to migrants out of economic, security-related, and political concerns, among them the fallout of the financial crises, anxiety about the implications of irregular migration on domestic security, and the rising tide of racism and growing influence of anti-immigration parties. Anti-immigrant sentiment has been a major driver of the electoral rise of the far right in several European states,[84] and under pressure from populist currents, European migration and asylum policies have become more security-oriented, which will negatively affect not only access to European soil, but also migrants and asylum seekers who have been waiting for years to resolve their status.

These challenges will have repercussions for the human rights approach to migration and asylum, which could end up prioritising economic and political gains over the strategic empowerment of the rights and freedoms of migrants and refugees. Amid new attitudes towards migration policies in Europe and the volatility of the EU’s relations with countries of origin and transit, Europe is increasingly inclined to impose security-based settlements that infringe the rights of undocumented migrants, with grave implications for the conditions of displaced migrants.[85]

Morocco’s growing influence and its increasing say in the regional governance of migration allows for several economic and political advances, but in turn, it makes it necessary for it to bring national legislation in line with international law,[86] in order to ensure genuine parity in basic rights and access to public services among citizens and non-citizen residents. To this end, it should expedite the enactment of a comprehensive immigration law that comports with international conventions, in particular the GCM. That agreement provides for serious guarantees to consolidate migrants’ effective enjoyment of fundamental rights and freedoms, introducing requirements to simplify procedures for obtaining the personal documents necessary to access public services, especially with regard to obtaining and renewing residence certificates and facilitating the registration of new-borns, while putting in place proactive measures to avoid violations that might result from the arrest and deportation of irregular migrants.

Accordingly, Morocco should draft a framework law on the prevention of all forms of discrimination, including against undocumented migrants, as consistent with the constitution and its international obligations, while purging legislation of all manifestations of racism and discrimination against migrants. For example, Article 1 of Law 00.04 on compulsory basic education, which makes state-funded education conditional on Moroccan nationality, should be amended in line with Jordanian Law 17/2022 on children’s rights, which does not discriminate between Jordanian and non-Jordanian children in the enjoyment of basic rights, including the right to education. The family code should also include flexible requirements that guarantee the rights of the children of migrants without civil status documents and school certificates, similar to Lebanese legislation that allows a foreigner born on Lebanese territory to obtain a birth certificate and considers every child born in Lebanon to parents of unknown origin to be Lebanese. The same applies to the legal framework for migrant workers. The eradication of all forms of labour exploitation to which non-nationals are vulnerable requires changes to the labour law to stiffen the penalties associated with the exploitation of African workers and guarantee their right to organise. The Bahraini model offers a guide here: Law 19/2006 provided for the establishment of a labour market regulatory body tasked with developing a strategy for the employment of migrant workers that gives them the same benefits as citizens.[87]

Similarly, Draft Law 17.66 should be enacted to establish a legislative framework for asylum. The bill provides for the recognition of refugee status granted by the UNHCR, with due attention to the relevant constitutional requirements and the principles enshrined in the International Refugee Convention, but some of its provisions should be amended to define the term ‘refugee’ more clearly, set forth procedures for access to available services, simplify asylum procedures and put in place the necessary guarantees in the event that refugees violate their duties towards the host country, and narrow the scope of forced repatriation within minimum limits while setting guarantees for refugee rights.[88]

Mere procedural amendments are inadequate to formulate an effective legislative framework for migration and asylum. Rather the philosophy underpinning legislation concerning non-nationals must be reconsidered and revised to eliminate any vestige or manifestation of the criminalisation of human movements and to ensure that migration is treated as an opportunity to achieve development and promote cultural cross-fertilisation among peoples.[89] An effective framework must purge elements that fuel a security-based approach to undocumented migrants and provide for the necessary conditions to enhance mixing and mobility for migrants with legal status and avoid measures that entrench their isolation.[90] Separation can be counterproductive, as evidenced by the tensions seen between local communities and groups of migrants concentrated in some regions, for example in the Boukhalef area of Tangiers in 2014 and 2015 and in the vicinity of the Oulad Ziane bus station in Casablanca.[91]

Morocco has been able to improve its ranking on the Migration Governance Index[92] thanks to successive improvements in the legislative and regulatory frameworks for migration policy and its growing involvement in international and regional initiatives aimed at implementing human rights requirements in migration management. But new challenges dictate that it cleave more closely to the general framework for migration governance as defined by the IOM in 2015, showing greater attention to integration between all competent actors—the Ministry of Interior, the ministerial division in charge of Moroccans abroad and migration affairs, the Inter-ministerial Unit for Human Rights, the CNDH, and the Council of the Expatriate Moroccan Community—in order to ensure uniform decision-making on migration affairs, while taking measures to mainstream migration issues into national development strategies.[93] Participatory migration management must also be improved based on lessons learned from past experiences, which have demonstrated the limits of a participatory approach to the development and monitoring of migration programmes given the centralisation of outreach and awareness programmes. About two-thirds of migrants and refugees had no knowledge of government campaigns to resolve their status and facilitate their integration, and only about one-fifth of them were aware of the existence of a national strategy for migration and asylum.[94] Accordingly, the technical, financial, and managerial capacities of NGOs working on migration and representing migrants and refugees should be strengthened,[95] which would bolster the human rights dimension of migration policy and help combat various forms of discrimination against non-nationals, with the aim of making the relevant strategies and programmes more responsive to the actual needs of migrants and refugees.

At the political level, Morocco is trying to build its own model for migration management based on an approach that balances the political and humanitarian dimensions.[96] However, this approach runs up against constraints both internal—the shifting strategic directions of domestic migration policy—and external, particularly the way European parties continue to treat Morocco as a mere border guard tasked with serving Europe’s migration agenda, which spurs Morocco to institute measures detrimental to the status of African migrants.[97] Morocco thus must respond effectively and as is consistent with its priorities and regional commitments, such as the African Union Plan of Action (2018–2030), which urged member states to facilitate the safe and regular movement of persons,[98] and the African Union’s Agenda 2063, which calls for the free movement of individuals and the abolition of visas for all African citizens as a goal of African economic integration in the first decade of the implementation of the agenda.[99] Moreover, Morocco’s interest in joining African cooperation organisations such as the Economic Community of West African States and the African Continental Free Trade Area will obligate it to take measures guaranteeing the freedom of movement of persons between member states, which means the arrival of new waves of migrants.[100] In turn, this necessitates a review of migration cooperation programmes between Morocco and European countries with an eye to adopting a new approach that combines border protection with reasonable openness to the legal and sustainable movement of persons.[101] Here, lessons should be learned from past experiences that demonstrated the high cost of security arrangements and their role in fuelling irregular migration in a way that endangers the rights of migrants and promotes transnational crime.[102]

Nevertheless, these interventions will fail to fulfil the humanitarian entitlements in the management of human movements if they are not embedded within an integrated policy package that responds to the actual needs of migrants and refugees and is formulated in a participatory manner with the target groups.[103] This requires updating the national strategy for migration and asylum, whose multiple shortcomings have rendered it obsolete over the last decade, while working to incorporate migrants’ rights into various public policies, especially priority areas like health. Migrants should be covered by basic compulsory health insurance services and their access to public health services supported. Their right to education should be entrenched by incorporating the cultural, linguistic, and educational needs of migrants in school programmes and curricula aimed at foreigners, while children with migrant status should be given the same incentives as their Moroccan counterparts to encourage school attendance and discourage attrition. Cooperation with specialised international organisations should also be strengthened in light of the positive outcomes of the migration and protection programme implemented from 2018 to 2021 in conjunction with UNICEF and the EU.

Conclusion

This paper has attempted to trace Morocco’s approach to resolving the status of migrants and refugees, which has proceeded along two different trajectories, each with its own contexts and outcomes. The first was a strategically oriented trajectory that entailed elaborating a national strategy to bring migration policies in line with international conventions and thus make them more responsive to humanitarian considerations. This was translated into a legislative and regulatory framework for managing migration flows that was partially aligned with rights entitlements and coupled with an attempt to make the procedures for regularising the administrative status of migrants and refugees more attuned to the human rights approach. The second trajectory was of a more exceptional nature, entailing discrete, isolated measures that provided many irregular migrants with residence documents that enabled them to access some basic services, settled a significant number of asylum claims, and enabled refugees to integrate into the country’s economic and social fabric while assisting those who wish to move to other countries in coordination with the UNHCR.

At the same time, however, the weakness of the legislative and regulatory framework has undermined the effective empowerment of the rights of migrants and refugees whose status was resolved and limited their access to public services. The oscillation between strategic and exceptional measures reflects a hybrid policy that combines both open and restrictive approaches to migration: the open door policy is expressed in various reintegration, admission, and resettlement processes, while the restrictive policy is apparent in the tightened measures taken against migrants within the framework of cooperation and partnership programmes with Europe, whose posture on migration management starts from a defensive position based on the protection of its external borders.

To enhance the strategic orientation of migration policy, the frame of reference for migration management and asylum must be strengthened. The enactment of Draft Law 72.17 on migration and Draft Law 66.17 on asylum should be expedited after first updating them to enshrine rights safeguards while recognising Morocco’s strategic interests. Other legislation and regulatory statutes must be made consistent with international treaties, especially the GCM, and African governing principles for migration policies, in particular the Migration Policy Framework for Africa associated with the African Union action plan for 2018–2027. In addition, institutional and administrative guarantees for a rights-based approach to the management of migrant and refugee affairs should be strengthened by enhancing cooperation among the various actors involved in the governance of migration and asylum, with the aim of making strategies more responsive to the actual needs of migrants and refugees. Mechanisms for consultation and partnership between public authorities and stakeholders should be institutionalised by involving civic and advocacy groups defending the rights of undocumented migrants, which would enhance the participatory nature and effectiveness of migration policies.

The same confusion has affected the institutional side of the equation. The various bodies making, implementing, and evaluating migration policies are poorly integrated, and several ad hoc structures have been created to oversee some regularisation processes and reintegration programmes. The unsustainable, heterogeneous nature of the regulatory framework has adversely impacted the fulfilment of migrants’ rights, and this instability has moreover eroded of public authorities’ relationship with international organisations working on migration and civil society associations that defend migrants’ rights. As a result of this improvised, piecemeal approach—occasionally participatory, but largely not—many official solutions have not been adequately responsive to the expectations of migrants and refugees.

This article is originally written in Arabic for Rowaq Arabi.

[2] Abourabi, Yousra (2022) ‘Governing African Migration in Morocco’, in Dêlidji Eric Degila and Valeria Marina Valle (eds.) Governing Migration for Development from the Global Souths (Leiden: Brill), p. 47.

[3] Regragui, Othman (2022) ‘Maroc-Espagne: Partenariat Dynamique et Antagonisme Géostratégique’, Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique, Recherches et Documents 12, p. 4.

[4] In particular: Atouf, al-Kabir (2013) Al-Hijrat al-‘Alamiya wa-l-Maghribiya: Qadaya wa-Namadhij [Global and Moroccan Migrations: Issues and Examples] (Agadir: The Faculty of Arts and Humanities at the University of Ibn Zohr); al-Karini, Idris (2018) Al-Hijra fi Hawd al-Mutawassit wa-Huquq al-Insan [Migration in the Mediterranean Basin and Human Rights] (Marrakesh: Organisation d’Action Maghrébine); Nima Fayyad, Hisham (2022) al-‘Alaqa bayn al-Hijra al-Dawliya wa-l-Tanmiya: Min Manzur al-Buldan al-Mursila li-l-Muhajirin [The Relationship between International Migration and Development: From the Perspective of Migrant-Sending Countries] (Doha: Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies), https://www.dohainstitute.org/ar/BooksAndJournals/Pages/International-Migration-and-Development.aspx.

[5] Under Article 1 of the Geneva Convention of 1951, a refugee is any person outside his or her country of nationality due to a well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, and because of this fear is unwilling or unable to avail himself of the protection of that country. The UN defines a migrant as any person who has moved to a foreign country whether for voluntary or involuntary reasons and regardless of the person’s legal status, whether documented or undocumented.

[6] Gurieva, Lira, and Aleksander Dzhioev (2015) ‘Economic Theories of Labor Migration’, Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 6 (6), p. 104.

[7] Hagen-Zanker, Jessica (2008) ‘Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature’, Maastricht Graduate School of Governance Working Paper No. 2008/WP002, p. 7.

[8] Castles, Stephen, Hein de Haas, and Mark J. Miller (2014) The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World (New York: Guilford Press), p. 53.

[9] Massey, Douglas (2009) ‘The Political Economy of Migration in an Era of Globalization’, in Samuel Martinez (ed.) International Migration and Human Rights: The Global Repercussions of U.S. Policy (California: University of California Press), p. 25.

[10] Nima Fayyad, Hisham (2012) ‘Hijrat al-‘Amala min al-Maghrib al-‘Arabi ila Uruba’ [Labour Migration from North Africa to Europe] (Beirut: Arab Centre for Research and Policy Studies), p. 22–23.

[11] Mutawie, Mohammed (2015) ‘al-Ittihad al-Urubi wa-Qadaya al-Hijra: al-Ishkaliyat al-Kubra wa-l-Istratijiyat wa-l-Mustajiddat’ [The EU and Migration Issues: The Major Questions, Strategies, and New Developments], Majallat al-Mustaqbal al-Arabi 431, p. 39.

[12] Al-Sadiqi, Said (2013) ‘Tashdid al-Raqaba ‘ala al-Hudud wa-Bina’ al-Aswar li-Muharabat al-Hijra: Muqarana bayn al-Siyasatayn al-Amrikiya wa-l-Isbaniya’ [Tightening Border Surveillance and Building Walls to Combat Migration: A Comparison of American and Spanish Policy], Majallat Ru’an Istratijiya 3, p. 99.

[13] Adli Mansour, Ahmed (2019) al-Hadara al-Ta’iha [Civilisation at Sea] (Amman: Biruni for Publication and Distribution), pp. 275–276.

[14] Jaballah, Sofien (2023) ‘EU-Tunisian Policy of Managing Migration Across the Mediterranean: Addressing Regular and Irregular Flows’, Arab Reform Initiative, 20 June, accessed 5 July 2023, https://cutt.us/sfbRB.

[15] Huysmans, Jef (1998) ‘Dire et Écrire la Sécurité: Le Dilemme Normatif des Études de Sécurité’, Cultures & Conflits 31-32, pp. 177-178.

[16] De Haas, Hein (2010) ‘The Internal Dynamics of Migration Processes: A Theoretical Inquiry’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (10), p. 1,591.

[17] Nima Fayyad, Hashim (2018) ‘Mafahim Nazariya fi al-Hijra al-Sukkaniya: Dirasa Tahliliya Muqarina’ [Theoretical Concepts in Population Migration: An Analytical, Comparative Study], Majallat al-Umran 18 (7), pp. 25–26.

[18] Wickramasinghe, Aain, and Wijitapure Wimalaratana (2016) ‘International Migration and Migration Theories’, Social Affairs 1 (5), p. 24.

[19] Khachani, Mohamed (2017) ‘Hijrat al-Shabab al-‘Arabi ila Duwal al-Ittihad al-Urubi: Qira’a Naqdiya fi al-Siyasa al-Urubiya li-l-Hijra’ [Arab Youth Migration to EU States: A Critical Reading of European Migration Policy], Majallat al-Umran 21, p. 49.

[20] Roxy, Ashraf Milad (2021) ‘Refugees, the Internally Displaced, and Conflict Resolution, the Case of Libya’, Rowaq Arabi 24 (1), p. 10.

[21] UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (2013) ‘Violence, Vulnerability and Migration: Trapped at the Gates of Europe: A Report on Sub-Saharan Migrants in an Irregular Situation in Morocco’, accessed 19 April 2023, https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cmw/docs/ngos/MSF_Morocco18_Exec_Summ.pdf.

[22] Moroccan Human Rights Association (2020) ‘Problèmes Liés à la Détention des Migrants’, p. 6.

[23] Dahir No. 1.93.317 of 2 August 2022 on the publication of the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families, Official Gazette No. 6015, January 2012, accessed 16 May 2023, https://bit.ly/3q6AAX3.

[24] Hicks, Neil (2021) ‘The Impact of Counter-Terrorism Measures on Human Rights in the Middle East and North Africa’, Rowaq Arabi 26 (3), accessed 7 May 2023, https://doi.org/10.53833/VQBN9597.

[25] Law 02.03 on the Entry and Residence of Foreigners in the Kingdom of Morocco and Illegal Migration, Official Gazette No. 5160, 13 November 2003, p. 3,817, accessed 11 May 2023, https://bit.ly/420NNOH.

[26] CNDH (2013) ‘La Gouvernance des Migrations et Droits de l’Homme: La Nécessité d’Intégrer les Droits Fondamentaux des Migrants dans les Politiques de Migrations’, accessed 28 April 2023, https://cutt.us/bWuWS.

[27] CNDH (2013) ‘Etrangers et Droits de l’Homme au Maroc: Pour une Politique d’Asile et d’Immigration Radicalement Nouvelle’, pp. 3–4, accessed 17 April 2023, https://bit.ly/45oCRgq.

[28] Bensaad, Ali (2015) L’immigration Subsaharienne au Maghreb (Paris: National Centre for Scientific Research), p. 251.

[29] Global Compact on Refugees (2021) ‘An Overview of How the Global Compact on Refugees is Being Turned into Action in Morocco’, 15 March, accessed 11 May 2023, https://bit.ly/3KqsBZN.

[30] Alali, Hisham (2023) ‘al-Muzawaja bayn al-Bu‘dayn al-Ijtima‘i wa-l-Amni fi al-Ta‘amul ma‘ Qadaya al-Hijra fi al-Tajriba al-Maghribiya’ [Mixing the Social and Security Dimension in Addressing Migration Issues in the Moroccan Experience], in Said al-Haji and al-Habib Astati Zayn al-Abidin (eds.) al-Hijra al-Dawliya fi Siyaqat Mutaghayyira [International Migration in Changing Contexts] (Agadir: Dar al-Irfan for Publication and Distribution), p. 190.

[31] IOM (2018) ‘Migration et le Programme 2030, Corrélations Complètes Entre les Cibles des ODD et la Migration’, p. 16, accessed 16 April 2023, https://bit.ly/3Wm6Odf.

[32] Law 27.14 on the Suppression of Human Trafficking, issued with Dahir No. 1.16.127 of 25 August 2016, Official Gazette, No. 6501, 9 September 2016.

[33] Cruz Zúñiga, Pilar (2020) La Traite des êtres Humains en Andalousie, au Maroc et au Costa Rica: Une Approche Comparative (Madrid: Dyckinson), p. 61.

[34] CNDH (2013) ‘Etrangers Et Droits de l’Homme au Maroc’.

[35] Ben Radi, Malika (2018) ‘al-Waqaya min In‘idam al-Jinsiya ‘ind al-Muhajirin wa-Atfalihim bi-Shamal Ifriqiya’ [Preventing Statelessness among Migrants and Their Children in North Africa], Moroccan Association for Studies and Research on Migration, p. 39.

[36] Claiming asylum involves several steps. In the first phase, the UNHCR accepts a registration form and considers it after interviewing the asylum seeker. If the claim is denied, four weeks are given to file an appeal and ask the UNHCR to reconsider the file, whereupon it will issue a final decision not subject to appeal. If the claim is accepted, the UNHCR follows up on it through the Office for Refugees and Stateless Persons, which, after examining the file, grants refugee status. In the event of a denial, the injured party can turn to the office’s grievance committee within thirty days of receiving the denial.

[37] Elmorchid, Brahim, and Hind Hourmat-Allah (2018) ‘Le Maroc Face au Défi des Réfugiés Economiques: Quelle Approche Pour Quelle Gouvernance Migratoire?’, Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 2 (3), p. 241.

[38] Lahlou, Mehdi (2015) ‘Morocco’s Experience of Migration as a Sending, Transit and Receiving Country’, Instituto Affari Internazionale, p. 3, accessed 29 April 2023, https://bit.ly/3KknGJV.

[39] Mohammedi Ilwi, Youssef (2018) ‘Dawr ‘Amaliyat Taswiya Wad‘iyat al-Ajanib fi Tadbir Tadaffuqat al-Hijra’ [The Role of the Regularisation Process for Foreigners in Managing Migration Flows], al-Majalla al-Maghribiya li-l-Idara al-Mahalliya wa-l-Tanmiya 140, p. 159.

[40] Initially in the second phase of the exceptional regularisation process, 20,000 applications were approved. This number increased to 23,000 in 2018 after claims were reconsidered by the National Appeals Committee, which relied on less stringent criteria to resolve the status of irregular migrants.

[41] Kingdom of Morocco (2022) Taqrir bi-Rasm al-Jawla al-Rabi‘a li-l-Isti‘rad al-Dawri al-Shamil al-Muqaddim li-l-Dawrat al-Hadiya wa-l-Arba‘in li-Majlis Huquq al-Insan bi-Jinif [Report on the Fourth Round of the Universal Periodic Review Presented in the Forty-First Session of the Human Rights Council in Geneva], p. 27.

[42] Lemaizi, Salaheddine (2022) ‘Politique Migratoire au Maroc Entre Pressions Européennes et Chantage Marocain’, Maghreb Action on Displacement and Rights, p. 16.

[43] Al-Hamdouni, Khaled (2019) ‘al-Siyasa al-Jadida li-l-Maghrib fi Majal al-Hijra wa-Ishkaliyat Idmaj al-Muhajirin’ [Morocco’s New Migration Policy and the Integration of Migrants], in Zahirat al-Hijra ka-Azma ‘Alamiya bayn al-Waqi‘ wa-l-Tahaddiyat [Migration as a Global Crisis between Reality and Challenges], Arab Democratic Centre, p. 262.

[44] Kingdom of Morocco.

[45] United Nations (2020) Situation Report on International Migration 2019: The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration in the Context of the Arab Region, accessed 11 May 2023, https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/situation-report-migration-2019-en.pdf.

[46] Anouzla, Leila (2022) ‘Hasilat al-Idmaj al-Iqtisadi li-l-Muhajirin al-Mustaqirrin bi-l-Maghrib’ [Outcome of the Economic Integration of Migrants Settled in Morocco], al-Sahraa, 27 June, accessed 5 July 2023, https://bit.ly/3piPJor.

[47] Ministry for Foreign Affairs, African Cooperation, and Expatriate Moroccans (2022) Mashru‘ Naja‘at al-Ada’ [Healthy Performance Project], p. 43.

[48] Organisation for German Cooperation in Morocco (2019) ‘Gestion des Migrations et Intégration, Coopération et Migration au Service du Développement’, accessed 9 May 2023, https://bit.ly/3CjFZwb.

[49] Lahou, Sabri (2016) ‘al-Maghrib wa-l-Hijra al-Qadima min Ifriqiya Janub al-Sahra’’ [Morocco and Migration from Sub-Saharan Africa], Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, 21 December, p. 8, accessed 18 April 2023, https://bit.ly/3vnqq5f.

[50] Benjelloun, Sara (2020) ‘Min Ajl Nizam Watani Fa‘al li-l-Luju’ Yadman al-Huquq al-Mu‘atarafa bi-ha Dawliyan li-l-Laji’in wa-Talibi al-Luju’’ [For the Sake of an Effective National Asylum System That Guarantees the Internationally Recognised Rights of Refugees and Asylum Seekers], Heinrich Boll Foundation, p. 27.

[51] Ben Radi, p. 42.

[52] World Bank (2022) ‘Refugee Population by Country or Territory of Asylum’, accessed 22 May 2023, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SM.POP.REFG.

[53] UNHCR (2022) ‘Refugee Data Finder’, accessed 22 May 2023, https://www.unhcr.org/refugee-statistics/.

[54] UNHRC (2022) ‘Awda‘ al-Laji’in wa-Talibi al-Luju’ bi-l-Maghrib’ [Situation of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Morocco], accessed 22 May 2023, https://www.unhcr.org/ar/5ae5bee44

[55] Higher Planning Commission (2019) al-Sukkan wa-l-Tanmiya fi al-Maghrib: Khams wa-‘Ishrin Sana ba‘d Mu’tamar al-Qahira [Population and Development in Morocco: Twenty-five Years after the Cairo Conference], p. 95.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Latrech, Oumaima (2021) ‘UNHCR, EU, Hail Morocco’s Commitment to Protecting Refugees’, Morocco World News, 8 December, accessed 12 May 2023, https://bit.ly/3tx8SB7.

[58] Khachani, Mohamed (2019) La Question Migratoire au Maroc, Moroccan Association for Research and Studies on Migrations, p. 191.

[59] CNDH (2022) ‘La Stratégie Nationale d’Immigraton et d’Asile et l’Impératif d’Harmonisation du Cadre Juridique’, 23 June, accessed 19 April 2023, https://www.cndh.ma/fr/communiques/les-jeudis-de-la-protection-la-strategie-nationale-dimmigration-et-dasile-et-limperatif.

[60] Lemaizi, Salaheddine (2023) ‘Profil Migratoire du Maroc: 5 Chiffres Pour Comprendre’, 9 January, accessed 7 July 2023, https://bit.ly/3JwmaXs.

[61] Economic, Social, and Environmental Council (2018) ‘Migration et Marché du Travail’, p. 14, accessed 18 May 2023, https://bit.ly/3WpBVo8.

[62] CNDH (2022) Tada‘iyat Kufid 19 ‘ala al-Fi’at al-Hashsha wa-Masarat al-Fi‘liya [Repercussions of Covid-19 on Vulnerable Groups and Paths of Effectiveness], p. 141, accessed 10 May 2023, https://bit.ly/3ooB0I2.

[63] Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network (2018) ‘Maroc: Droits Economiques et Sociaux des Personnes Migrantes et Refugiées’, p. 10.

[64] The right of the children of migrants to an identity is constrained by various administrative factors, including the difficulty of obtaining official documentation of the origins of unaccompanied minors and the refusal of some departments to register new-borns of undocumented migrant parents, as well as other legislative issues, such as proof of paternity for children born outside wedlock. The problems associated with exercising this right impact other cultural, economic, and social rights.

[65] Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network.

[66] CNDH (2020) al-Taqrir al-Sanawi ‘an Halat Huquq al-Insan bi-l-Maghrib li-Sanat 2019: Fi‘liyat Huquq al-Insan Dimn Namudhaj Nashi’ li-l-Hurriyat [Annual Report on the State of Human Rights in Morocco 2019: The Effectiveness of Human Rights within an Emergent Paradigm of Liberties], p. 41, accessed 17 May 2023, https://bit.ly/3Miyyuo.

[67] Economic, Social, and Environmental Council, p. 14.

[68] Ibid.

[69] CNDH (2015) ‘Intégration des Migrants au Maroc: Appel à une Stratégie Intégrée Impliquant Tous les Acteurs Concernés’, 28 May, https://www.cndh.org.ma/fr/article/integration-des-migrants-au-maroc-appel-une-strategie-integree-impliquant-tous-les-acteurs.

[70] Ait Ben Lmadani, Fatima (2016) ‘La Politique d’Immigration. Un Jalon de la Politique Africaine du Maroc? Cas de la Régularisation des Migrants Subsahariens’, Moroccan Association for Studies and Research on Migration, p. 21.

[71] Merrouni, Saad Alami (2019) ‘Migrant Women in Morocco: A Gender-Based Integration Strategy?’, Hijra 4, pp. 86–87.

[72] Halim, Aisha (2022) ‘al-Hijra al-Nisa’iya min Ifriqiya Janub al-Sahra’: al-Jindar wa-Ishkaliyat Tadbir al-‘Unf al-‘Abir li-l-Hudud’ [Female Migration from Sub-Saharan Africa: Gender and the Management of Cross-Border Violence], al-Majalla al-Arabiya li-l-Nashr al-Ilmi 49, pp. 321–322.

[73] Civic Council Against All Forms of Discrimination (2019) État des Lieux des Discriminations au Maroc, pp. 74–75.

[74] Manby, Bronwen (2019) ‘Preventing Statelessness among Migrants and Refugees: Birth Registration and Consular Assistance in Egypt and Morocco’, LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series no. 27, accessed 21 May 2023, https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/101091/26/PreventingStatelessnessAmongMigrants.pdf.

[75] Higher Planning Commission (2022) ‘Note sur les Résultats de l’Enquête Nationale sur la Migration Forcée de 2021’, p. 7, accessed 13 May 2023, https://bit.ly/3CidzTe.

[76] CNDH (2020), p. 42.

[77] Al-Murabet, Said (2022) ‘Tahqiq: Yawm al-Jum‘a al-Dami: al-Qissa al-Kamila li-Ma Jara ‘ind al-Siyaj al-Fasil bayn al-Nazur wa-Maliliya’ [Expose: Bloody Friday: The Full Story of What Happened at the Fence between Nador and Melilla], Hawamich, 2 July, accessed 13 May 2023, https://hawamich.info/4331/.

[78] CNDH (2022) I‘adat Tartib al-Awlawiyat li-Ta‘ziz Fi‘liyat al-Huquq [Rearranging Priorities to Promote Effective Rights], p. 136.

[79] The Office for Refugees and Stateless Persons has not operated consistently since its establishment in 1957. Its operations were suspended in 2004 and the office only reopened with the exceptional regularisation process for refugees in September 2013. It later ceased operations for twenty months from April 2017 to December 2018, and proceedings were also suspended throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. It only resumed regular operations in early 2022. The reasons for this are unknown, but it is thought to be related to the postponement of the asylum law, as well as the desire to slow down the recognition process for the refugees who came in increasing numbers in recent years, especially from Arab countries like Syria and Yemen.

[80] Khachani (2017), p. 51.

[81] Economic, Social, and Environmental Council.

[82] IDMC (2020) Global Report on Internal Displacement 2020, p. 15, accessed 28 April 2023, https://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/2020-IDMC-GRID.pdf.

[83] World Bank (2018) Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration, p. xxi, accessed 22 April 2023, file:///Users/macbook/Downloads/WBG_ClimateChange_Final.pdf.

[84] Sadayri, Nabil (2021) ‘al-Tahaddiyat al-Amniya wa-l-Tadbir al-Istratiji li-l-Hijra ghayr al-Nizamiya bi-l-Maghrib’ [Security Challenges and the Strategic Management of Irregular Migration in Morocco], Arab Democratic Centre, p. 3.

[85] IOM (2019) ‘Middle East and North Africa Regional Strategy 2020–2024’, p. 15, accessed 2 May 2023, https://mena.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl686/files/documents/Middle%20East%20and%20North%20Africa%20Regional%20Strategy%202020-2024_21Sept20_v06_0.pdf.

[86] Hajji, Mustafa (2021) ‘Hal al-Maghrib bi-l-Fi‘l Darki Uruba?’ [Is Morocco Really Europe’s Policeman?], Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis, 12 August, accessed 29 April 2023, https://mipa.institute/8653.

[87] IOM (2021) ‘The Arab Regional GCM Review Report: Progress, Priorities, Challenges and Future Prospects’, p. 20.b

[88] CNDH (2021) al-Taqrir al-Sanawi hawl Halat Huquq al-Insan bi-l-Maghrib li-Sanat 2020 [Annual Report on the State of Human Rights in Morocco 2020], p. 116, accessed 16 May 2023, https://bit.ly/3OD9Tnd.

[89] UN (2014) Ishkaliyat al-Hijra fi Siyasat wa-Istratijiyat al-Tanmiya fi Shamal Ifriqiya: Dirasa Muqarina [Migration Issues in Development Policies and Strategies in North Africa: A Comparative Study], p. 71.

[90] Al-Zuaytrawi, Mustafa (2018) ‘al-Hijra, al-‘Amal al-La’iq wa-l-Huquq al-Ijtima‘iya fi al-Maghrib: Dalil Muwajjih li-l-Niqabat wa-l-‘Ummal al-Muhajirin’ [Migration, Decent Work, and Social Rights in Morocco: A Guide for Unions and Migrant Workers], International Institute for Cooperation and Development, p. 20.

[91] Boukhasas, Mohammed Karim (2020) ‘al-Muhajirun ghayr al-Nizamiyin wa-Kuruna: al-Mu‘ana al-Muzdawija’ [Undocumented Migrants and Covid-19: A Double Hardship], Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis, 15 September, accessed 5 July 2023, https://mipa.institute/9348.

[92] IOM (2017) ‘Migration Governance Profile: Kingdom of Morocco’, p. 1, accessed 22 June 2023, https://bit.ly/3MQa5MG.

[93] Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (2017) ‘Interactions Entre Politiques Publiques, Migrations et Développement au Maroc’, p. 55, accessed 7 May 2023, https://bit.ly/3sL61Fp.

[94] Higher Planning Commission (2022), pp. 20–21.

[95] Mouna, Khalid, Noureddine Harrami, and Driss Maghraoui (2017) L’immigration au Maroc: Les Défis de l’Intégration (Meknes: Moulay Ismail University), p. 83.

[96] El Dahshan, Mohamed, and Mohammed Masbah (2020) ‘Synergy in North Africa: Furthering Cooperation’, Chatham House, January, accessed 18 May 2023, https://bit.ly/3hPj3eD.

[97] In this regard, I note the attempt by 1,500 migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa to cross the border fence between Nador and Melilla on 24 June 2022, which resulted in injuries among the migrants. The incident took place at a time of improvements in the Moroccan-European partnership following a period of deadlock in 2020 and 2021, during which raids made by the Moroccan authorities on migrant camps fell from 380 in 2018 to just 37 in 2020–2021. See Moroccan Human Rights Association (2022) ‘al-Tasrih al-Sahafi al-Khass bi-l-Ahdath al-Ma’sawiya li-Yawm al-Jum ‘a 24 Yunyu 2022’ [Press Statement on the Tragic Events of Friday, 24 June 2022], 20 July, accessed 7 July 2023, www.amdh.org.ma/contents/display/532.

[98] Al-Habib, Nader (2018) ‘La Politique Marocaine de la Migration, à l’Aune de l’Adhésion du Royaume du Maroc à la CEDEAO’, in La Question Migratoire en Afrique: Enjeux, Défis et Stratégies (Rabat: Royal Institute for Strategic Studies), pp. 19–20.