BRICS and Human Rights: Issues, Implications, and Impact Scenarios Under Expansion

Citation: Khalifa, Ahmed A., Zainab Fathy (2024) ‘BRICS and Human Rights: Issues, Implications, and Impact Scenarios Under Expansion’, Rowaq Arabi 29 (1), pp. 145-162, DOI: 10.53833/WJPV7193.

Introduction

BRICS studies[1] highlight the extensive debate surrounding the nature of the group, its ultimate goals, and the status of certain issues within its framework. At the heart of the debate lies the dispute over defining the group: Is BRICS an anti-Western coalition opposed to the hegemonic US-led order? Or is it a group striving to build a new global system that genuinely addresses injustice and inequality among nations? Most studies agree that BRICS represents a model of South-South cooperation and that it supports global reform, progressive change, and equality.[2]

Since the group’s inception in 2009 until the latest summit held in Johannesburg in August 2023, members have insisted on developing pragmatic cooperation based on the principle of ‘solidarity rather than unity or uniformity’. This cooperation spans multiple fields, with commitments, choices, and policies stemming from the commonalities among members. These commonalities include a desire for development and shared general orientations in economy, trade, and international economic relations, despite a lack in many shared political values, historical experiences, or local traditions.[3]

The inclusion of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iran, Egypt, and Ethiopia—most of which have political systems ranking low on human rights and political freedom indices[4]—into the BRICS group starting in January 2024 has raised several questions regarding the relationship between the BRICS expansion and the status of human rights issues within the group, as well as the positions of its member states on these issues globally.

Previous studies show the group’s approach to human rights issues. Maria Freire notes that despite the differences in political systems among BRICS countries, they all share a sensitivity towards the imposition of human rights and democracy from external sources. Nonetheless, they do express an interest in human rights issues.[5] This interest is constrained by internal differences between Brazil, India, and South Africa on one hand, and China and Russia on the other.[6] While some studies portray human rights and democracy issues, along with specific regional, border, and maritime disputes, as the main challenges facing BRICS, they also highlight the group’s ability to adopt ‘coordinated/unified’ policies towards the global order.[7] Ian Taylor points out that BRICS countries do not prioritise the promotion of human rights in Africa; instead, their presence on the continent is driven by their own economic and political interests, with human rights ranking low on their list of priorities.[8]

This debate draws us to two conclusions that pave the way for the study of this topic. The first indicates that BRICS, as a model of South-South cooperation, adopts a pattern distinct from the Western model in terms of development, rights, and cooperation. The second highlights that human rights issues are of interest within the BRICS framework and its member states. However, in previous studies, this interest has been framed within a broader focus on the group’s political dimensions and the areas of agreement and disagreement among its members. This further suggests that these observations are derived more from experience and observation rather than extensive study. Taylor’s study is an exception, as it attempted to provide a deeper insight into BRICS countries’ policies in Africa from the perspective of the interplay between capital and human rights.

Accordingly, the study hypothesises that the expansion of BRICS, by including countries with a low interest in human rights issues, is consistent with human rights conditions within the member states and their interaction with global human rights issues.

The study employs the concepts of coherence and consistency[9] as a theoretical framework to deepen the understanding of this topic and test its hypothesis. Coherence in foreign policy refers to the ‘integrated use of economic, military, and diplomatic policies and tools to achieve the overarching goal of a particular state or group’.[10] At the policy-making level, it means ‘directing policies towards a specific agenda of priorities and objectives’. Consistency, on the other hand, refers to the ‘absence of contradictions within the external activities of the member states in various areas of foreign policy’.[11] Thus, consistency relates to the nature of outcomes, ensuring they are aligned among the member states, while coherence pertains to the policy-making process and its direction towards a specific goal.

To test this hypothesis, the study adopts a composite methodology that includes both qualitative and quantitative content analysis. The aim is to analyse the outcomes of various BRICS summits, extract the group’s perspective on human rights, and identify points of convergence and divergence with Western views on these issues. Additionally, the study employs an inductive approach to trace and outline the voting patterns of BRICS member states in the United Nations General Assembly, the UN Security Council and the Human Rights Council. The study further utilises results from reputable international reports assessing indicators of human rights and political and civil freedoms in the countries of interest.

This study is divided into four sections. First, it examines the position of human rights issues within BRICS, clarifying the group’s overall perspective on these issues and its relationship with the Western human rights system. Second, it explores the implementation of this perspective within member states, addressing the debate around human rights conditions in these countries and their significance in domestic policymaking. Third, it investigates how member states interact with international and multilateral mechanisms related to human rights. Finally, it explores potential scenarios for the status of human rights issues within BRICS and their implications for the future of the group’s expansion.

BRICS Human Rights Vision and the Challenge to the Prevailing Western Value System

Since its establishment, BRICS has represented a challenge to the current international system with its prevailing values and economic structures dominated by the ‘West’. Issues of democracy and human rights are among the topics for which BRICS and its prominent members (Russia and China) have offered an alternative perspective. BRICS’ discourse generally emphasises collective economic and social rights, moving away from the dominance of developed countries and the West over global resources, and aiming for justice and equality on an international level. This stance has made the group appealing for many countries in the Global South.

One study analysing the outcomes of BRICS summit data from 2009 to 2022 found that the number of commitments related to human rights during this period was twenty-six (2.49 per cent), while commitments related to climate change and the environment totalled thirty-seven (4.08 per cent), out of a total of 1,004 commitments recorded in the same period.[12] The majority of these commitments were focused on issues of international cooperation, global institutional reform, crime and corruption, and terrorism and regional security, accounting for over ninety per cent of the group’s total commitments. This highlights the group’s clear prioritisation of security and political issues over human rights.

Data from the height of the crises in Syria, Libya, and Sudan indicate that BRICS countries, including Russia, have consistently avoided military intervention in conflicts in the Middle East and Africa,[13] despite the presence of the Russian government-supported Wagner Group in many of these countries under the pretext of combating terrorism. The Russian Foreign Minister had praised Wagner’s positive role in the region as a significant military wing in the Russia-Ukraine war,[14] despite its negative impact on prolonging conflicts and worsening humanitarian conditions in the countries where it operates. Furthermore, none of the group’s statements have indicated support for any democratic transition or calls for sanctions related to human rights violations.[15]

Based on this, it can be said that BRICS aims to build a system of human rights standards based on several pillars, which can be summarised as follows:

- Rejection of the politicisation of human rights logic by international organisations and Western countries. The XV BRICS Summit Johannesburg II Declaration (August 2023) emphasised the need to ‘promote, protect and fulfil human rights in a non-selective, non-politicised and constructive manner and without double standards. We call for the respect of democracy and human rights. In this regard, we underline that they should be implemented on the level of global governance as well as at national level’.[16]

- Linking human rights to international multipolarity. BRICS declarations repeatedly affirm member states’ commitment to ‘inclusive multilateralism and upholding international law, […] and promoting cooperation based on the spirit of solidarity, mutual respect, justice and equality’. They further reject ‘the use of unilateral coercive measures, which are incompatible with the principles of the Charter of the UN and produce negative effects notably in the developing world […] and enhancing and improving global governance by promoting a more agile, effective, efficient, representative, democratic and accountable international and multilateral system’.[17]

- Linking human rights to the right to development.[18] Member states agreed to ‘continue to treat all human rights including the right to development in a fair and equal manner, on the same footing and with the same emphasis’.[19]

- Emphasising the links between economic rights (specifically economic rights of the state) and social and political rights. Member states stress the connection between economic rights, social rights, and political rights for individuals, highlighting their role in ensuring human rights for everyone regardless of their geographic region. This is based on the premise that achieving economic and sustainable development inevitably leads to improvements in human rights conditions. They assert that economic development is the driving force for progress in all other areas, especially political ones.

- Focusing on collective rights related to reducing poverty and hunger. The emphasis is on achieving equality among people, and ensuring access to energy, clean water, food, basic healthcare services, and education. This includes addressing the impacts of climate change and combating the spread of pandemics.[20]

- Emphasising women’s empowerment and their participation in development. This involves women’s increased involvement in peace processes, including conflict prevention and resolution, peacekeeping and peacebuilding, and post-conflict reconstruction and development.[21]

- Respecting the cultural specificity of each country and acknowledging each nation’s right to choose its own development model that preserves traditional values of local communities as an essential part of human rights protection within the country.[22]

- Ending Western hegemony over global life and systems[23] by rejecting external interventions and promoting the role of regional mechanisms in addressing existing problems based on cooperation among Global South countries.[24]

These pillars align with observations made by those analysing the human rights framework within BRICS. Many of these principles are derived from the Chinese discourse, specifically the current leadership vision of Xi Jinping regarding human rights.[25] This has led some to assert that ‘BRICS is merely a form of cooperation centred around China’. [26] These principles significantly diverge from the prevailing Western values regarding human rights. They uphold the dominance of the state, with its governmental and official apparatus, over human rights matters. In other words, the emphasis is on ‘the right of the state’ versus ‘the right of the individual’.

BRICS’ focus on social and economic rights, rather than on individual civil and political rights—including democratic rights—places it in direct contradiction with the United States and Western human rights perspectives. The Western view asserts that development cannot occur without protecting individual human rights and a supportive local environment enriched with principles of good governance and respect for basic civil and political rights.[27] This has led to the Western rejection of the term ‘right to development’ and the human rights values promoted by BRICS, especially considering interpretations and goals underlying their endorsement. This opposition is particularly pronounced through BRICS’ appeal to many developing countries eager for such anti-Western rhetoric.

Human Rights within BRICS+: Internal Disparities or Obstructive Contexts?

This section explores coherence regarding human rights conditions within BRICS+ member states after expansion, and the associated policymaking processes. It begins with an overview of human rights conditions within these countries according to indicators of civil and political freedoms, and democracy, and how this reflects on the status of human rights in their agendas as a guiding factor in their foreign policies. Table 1 illustrates the condition of the public sphere and civil society freedoms in BRICS+ countries.

Table 1: State of Civic Space and Civil Society Freedoms in BRICS+ Countries

| Classification | Country |

| Restricted | Brazil |

| Restricted | South Africa |

| Repressed | India |

| Closed | China |

| Closed | Russia |

| Repressed | Ethiopia |

| Closed | Saudi Arabia |

| Closed | Egypt |

| Closed | UAE |

Source: CIVICUS[28]

According to the CIVICUS Monitor, the classification of the state of civic space is based on respect for laws, policies, and the practice of fundamental freedoms such as the freedom of association, peaceful assembly, and freedom of expression, as well as the extent to which the state protects these basic rights. This classification uses a scale of five descriptors: Open, Narrowed, Restricted, Repressed, and Closed. These descriptors range from Open (free) to Closed, with the latter referring to environments where civic space faces severe hostility.[29]

According to reports on the group, China and Russia are classified in the worst category regarding the state of civic space (Closed). This indicates that the civic space in those countries is so severely restricted that the government and actors affiliated with it routinely imprison, abuse, and possibly kill individuals with impunity, for merely seeking to exercise basic freedoms of peaceful assembly, expression, and association. It is noted that four of the five countries who recently joined the group have a history of imprisoning and persecuting political opponents and civil society activists involved in exposing corruption and human rights abuses. The situation in Ethiopia – the fifth country – is not much better; numerous human rights violations have occurred during the ongoing conflict between the federal government and rebel forces in the Tigray region.[30]

From this perspective, CIVICUS questioned BRICS’ vision of the world and the values that unite its old and new members, suggesting that their only commonality is ‘repression’. They view the expansion of BRICS as contributing to the formation of an ‘international repressive alliance’.[31]

Table 2: Classification of BRICS+ Countries in the Human Freedom Index and the Global Freedom Index (Freedom House)

| Points on the Global Freedom Index (out of 100 Countries) | Ranking on the Human Freedom Index (2023) out of 165 Countries | Country |

| 72 | 73 | Brazil |

| 79 | 73 | South Africa |

| 66 | 91 | India |

| 13 | 121 | Russia |

| 9 | 149 | China |

| 18 | 125 | UAE |

| 20 | 148 | Ethiopia |

| 8 | 157 | Saudi Arabia |

| 18 | 159 | Egypt |

| 11 | 161 | Iran |

Source: Freedom House Map (2024)[32] and Human Freedom Index Report (2023)[33]

According to the Human Freedom Index, Iran, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia are among the ten least free countries in the world. Table 2 shows that seven out of the ten BRICS+ countries are classified as ‘not free’, while one country – India – is categorised as ‘partly free’, while South Africa and Brazil are considered ‘free’. This shows that BRICS’ expansion not only overlooked the human rights conditions of the joining countries but also established a majority of countries with poor human rights records. This emphasises the focus of BRICS member states on their specific interests at the expense of human rights issues.

Figure 1: Classification of Countries According to the Global Freedom Index

Source: Graph prepared by the researchers based on the Global Freedom Index.

Focusing on the countries with higher human rights ratings (South Africa, Brazil, and India), an analysis of their foreign policies and guiding principles indicates that they do not prioritise promoting human rights in their international relations.[34]

The issuance of an arrest warrant by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for Russian President Vladimir Putin and Russia’s Commissioner for Children’s Rights, Maria Lvova-Belova, on 17 March 2023, for alleged war crimes related to the forced transfer of children from Ukraine to Russia, created a diplomatic dilemma and controversy in South Africa, which hosted the BRICS summit in August 2023. The Gauteng High Court ruled two days after the warrant was issued that South Africa, as a member of the ICC, was obligated to arrest Putin if he arrived in Johannesburg. However, Putin did not attend the summit.[35] South African President Cyril Ramaphosa faced criticism for his silence on human rights abuses by BRICS members and the status of human rights in the country’s foreign policy agenda. Local and international civil society organisations in Johannesburg also protested human rights violations in the countries participating in the summit.[36]

Despite South Africa, Brazil, and India scoring higher in civil liberties, political freedoms, and democracy indicators compared to China and Russia, which rank among the poorest in these metrics, these ‘democratic’ countries still face accusations of serious human rights violations. These include issues such as high numbers of prisoners, harassment of human rights defenders, restrictions on civil society activities, and persecution of certain groups, particularly Muslims in India and migrants in Brazil. Recent international reports have noted a general deterioration in human rights conditions even in these countries, along with internal criticism regarding the status of human rights in their foreign policy agendas. This suggests a degree of coherence in policymaking across different BRICS+ countries concerning the role of human rights in their foreign policy, as all these countries generally place human rights at a low priority.

Interaction of BRICS Countries with Global Human Rights Issues: Models and Implications

This section examines the extent to which the views of BRICS countries on human rights are consistent with their mutual moral commitments, and the complex relationships between them. This includes assessing their positions on human rights issues, both within their own countries and in relation to allied nations, by analysing patterns of interaction with specific issues, and their voting behaviour in the Security Council, General Assembly, and Human Rights Council of the United Nations.

Regarding human rights violations in China—specifically the persecution of the Uighur ethnic group based on religion and the policies aimed at ‘Sinicising Islam’[37]—the BRICS countries, both the original and the newly joined members, have avoided issuing explicit criticisms of China. Brazil, for instance, has consistently declined to support statements expressing concern over China’s crimes against humanity towards the Uighurs in Xinjiang.[38]

Additionally, BRICS countries have either rejected or abstained from voting on discussions about China’s violations against the Uighurs at the Human Rights Council in October 2022.[39] In early 2023, China hosted a delegation of official religious scholars from fourteen Islamic countries, including Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia, who praised the conditions for Muslims in the region.[40]

The stance of BRICS countries on the Russian war in Ukraine is similarly aligned; no serious steps were taken to condemn Russia or denounce the humanitarian situation in Ukraine. Despite Brazilian President Lula da Silva offering to mediate peace talks to end the war, he stated that both Kyiv and Moscow were equally responsible for the conflict.[41] The close ties between Russia and BRICS countries—particularly with China—have provided Moscow with alternative economic opportunities to dealing with the West amid the imposed sanctions.[42]

In the same vein, the response of these countries to the death of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny—whose death led to criticism of the Kremlin for attempting to poison him and imprisoning him under harsh conditions that contributed to his death—further illustrates the solidarity of the BRICS countries with Moscow. China deemed Navalny’s death a ‘domestic Russian matter’.[43] while Brazilian President Lula emphasised the need to investigate the incident before making accusations.[44] India and South Africa did not comment on the incident. Neither the original BRICS members nor the newly joined ones were among the forty-three countries that called for an independent international investigation into Navalny’s death during the fifty-fifth session of the Human Rights Council, which held Russian President Vladimir Putin fully responsible.[45]

The stance on the Palestinian issue and Israel’s expansion of settlements in the West Bank is among the matters that BRICS+ countries generally agree on. They have shown solidarity with calls for a ceasefire in Gaza, the sustained entry of aid into the territory, and the promotion of a two-state solution. South Africa has filed a case against Israel at the International Court of Justice, accusing it of committing violations under the Genocide Convention. All BRICS+ members supported the UN resolution for a humanitarian ceasefire in Gaza, with only India and Ethiopia abstaining from the vote.[46]

Studies tracking and analysing voting patterns of the original BRICS countries reveal a consistent alignment (solidarity) in their approaches to various issues, including human rights. Among the fifty-eight resolutions put to a vote in the UN Security Council in 2011, BRICS members’ votes were identical on fifty-six of them. Another study showed that, prior to September 2020 (the incident of Russia being accused of poisoning Navalny with a chemical substance), the ‘old’ BRICS members had never voted in favour of resolutions against Russia in the General Assembly,[47] whether concerning human rights situations in Crimea or regional security in Ukraine. The only condemnation of Russia was in a statement banning the use of chemical weapons by India, South Africa, and Brazil.

BRICS countries—both old and new—have abstained from voting on most resolutions condemning human rights violations in Iran, or have rejected them outright, at UN General Assembly sessions from 2006 until December 2022. China voted against all such resolutions (a total of seventeen times), India voted ‘against’ sixteen times and abstained once, while Brazil abstained from all. South Africa voted against seven of these resolutions and abstained on the others. Similarly, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Ethiopia mostly abstained from voting.[48]

The following table illustrates the voting patterns among BRICS countries that were represented in the Human Rights Council, namely China, South Africa, and India, as well as the countries that joined later, represented by the UAE, during the sessions held in 2023.

Table (3): Voting Trends of BRICS Countries in the Human Rights Council During 2023

| Issues | BRICS Countries’ Vote | Session Number and Date |

| Use of mercenaries as a means of violating human rights and exercising the right of peoples to self-determination | Approved by South Africa, China, India, and (UAE) | 54th Human Rights Council Session (11 September – 13 October 2023) |

| Human rights and unilateral coercive measures | Approved by South Africa, China, India, and (UAE) | |

| The right to development | Approved by South Africa, China, India, and (UAE) | |

| Human rights situation in the Russian Federation | Opposed by: China Abstained: South Africa, India, and (UAE) | |

| Response to the humanitarian crisis in Sudan | Opposed by: China and (UAE) Abstained: India and South Africa | |

| Combating religious hatred | Approved by South Africa, China, India, and (UAE) | |

| Enhancing international cooperation in the field of human rights | Approved by South Africa, China, India, and (UAE) | 53rd Session (19 June – 14 July) |

| Human rights situation in Belarus | Opposed by: China Abstained: South Africa, India, and (UAE) | |

| Contribution of development to the enjoyment of human rights | Approved by South Africa, China, and (UAE) Abstained: India | |

| Cooperation with Ukraine in the field of human rights | Opposed by: China Abstained: South Africa, India, and (UAE) | |

| Promoting human rights in South Sudan | Opposed by: China Abstained: South Africa, India, and (UAE) | 52nd Session (27 February – 4 April 2023) |

| Human rights situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territories | Approved by South Africa, China, India, and (UAE) Abstained: India | |

| Human rights situation in Iran | Opposed by: China Abstained: South Africa, India, and (UAE) | |

| Human rights situation in Syria | Opposed by: China Abstained: South Africa, India, and (UAE) | |

| Human rights situation resulting from Russian aggression | Approved by: (UAE) Opposed by: China Abstained: South Africa and India | |

| Human rights in the Occupied Syrian Golan | Approved by South Africa, China, India, and (UAE) | |

| The right of the Palestinian people to self-determination | Approved by South Africa, China, India, and (UAE) | |

| Israeli settlements in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and the Occupied Syrian Golan | Approved by South Africa, China, India, and (UAE) |

Source: Table prepared by the researcher based on the resolutions of the Human Rights Council put to vote.

The table above demonstrates a general consistency among BRICS+ countries that were part of the Human Rights Council during the sessions held in 2023. South Africa and India abstained from voting on resolutions opposed by China, while the three countries, along with the UAE (a newly joined member), supported issues related to the importance of the right to development, the situation of human rights in the occupied Golan Heights, and the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination. The only notable deviation from the general voting pattern of the BRICS countries was on the issue of human rights violations in Ukraine due to Russian aggression. The UAE supported the resolution, whereas China opposed it, and India and South Africa abstained from voting. Member countries consistently refused to condemn human rights violations in any state presented during these sessions. This again aligns with the BRICS perspective on human rights, which prioritises cultural specificity and their belief that the issue should predominantly be determined by state authorities.

Accordingly, the interactions of BRICS+ member countries with human rights issues, both within the member states and on the international stage—primarily the Human Rights Council—show significant consistency on two levels. The first level relates to the bilateral stances on human rights issues generally and within the member states specifically, where there is a general rejection of external interference and Western media narratives concerning human rights violations in these countries. The second level is reflected in the voting patterns among these countries in international institutions, particularly in the Human Rights Council.

BRICS Expansion and Human Rights Issues in the Group: Possible Scenarios

Expanding BRICS by adding new countries had been on the agenda of the group’s summits for several years, until it was resolved at the Johannesburg Summit in August 2023, which set the criteria for joining the group and approved the admission of five new countries. Over the years, several countries had applied for membership in BRICS, and others had expressed their intention to join the group in the future.[49]

Several possible scenarios regarding the future of human rights issues within BRICS, in the context of potential further expansion, can be outlined on the basis of three main factors:

- The prospects of BRICS expansion and the nature of the political systems of countries that will join or withdraw from the group.

- The internal coherence within each member state regarding the importance of human rights and its role in shaping policies.

- The consistency in the outputs and discourse of member states on the international level.

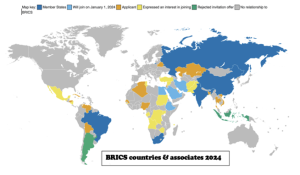

Map of Countries’ Relationships with the BRICS Group

Source: Anglicanism (2023).[50]

Source: Anglicanism (2023).[50]

Scenario 1: BRICS expansion to include countries with low human rights interest

This scenario assumes that BRICS will achieve further success after the accession of the five new countries, by demonstrating a significant degree of internal cohesion regarding maintaining the low prioritisation of human rights issues and achieving consistency in their foreign policy outcomes. BRICS might succeed in establishing a common currency, or at least settle exchanges among members in local currencies, as well as provide political support among BRICS countries in facing Western pressures to align with Western values on human rights issues. This could enhance solidarity voting in the General Assembly, the Security Council, and the Human Rights Council, which may contribute to increasing the interest of countries with low human rights priorities in joining the group.

However, this scenario faces several challenges. First, there is the potential failure of the group in achieving tangible results in enhancing its commercial cooperation, particularly regarding the establishment of a common currency. Second, increased Western pressures on countries closer to the West may prevent full integration among BRICS members, thereby limiting the political influence of anti-Western countries, especially Russia and China. Third, there is the challenge of whether China can continue to provide political support to both old and new members of the group with weak human rights records, such as Russia, Egypt, and Ethiopia, especially if they are experiencing economic difficulties. This may lead to continued pressure or conditionality from the West.

Scenario 2: BRICS expansion by including democratically governed countries

This scenario assumes that the current expansion of BRICS will achieve tangible success, enhancing cohesion among member countries and consistency in their foreign policy outcomes, while adopting a balanced approach to human rights issues and showing increased interest in developing them. This would be accompanied by a greater influence from South Africa, Brazil, and India, which, under internal pressures, would reorder domestic priorities and drive policymakers to place more emphasis on human rights in their international relations. Consequently, this scenario would facilitate the inclusion of countries with more open public spaces and democratic systems.

However, this scenario faces several challenges. The three countries mentioned are not aligned in their approaches to human rights, and they do not always act as a unified bloc either within BRICS or outside it. Additionally, China’s influence within BRICS is increasing over time, as newly joined countries have closer relations with China than with any other member. This makes this scenario less likely.

Scenario 3: BRICS declining role and reduced focus on human rights

This scenario posits that BRICS expansion may lead to counterproductive results within the group. While the countries focus on enhancing economic coordination among themselves, there will be a decline in political and human rights agendas. This decline will be accompanied by increased internal discrepancies due to ideological inconsistencies and differences in their international relations networks, especially with the growing number of countries that do not seek BRICS membership as an alternative to their ties with the West, but alongside it.

This scenario could materialise whether additional countries with diverse governance systems and interests are admitted to the group or if the current expansion pattern continues. It assumes a weakening of internal cohesion among member states regarding the status of human rights. Some countries within the group may focus more on promoting democracy and human rights in their policies, leading to a decrease in the overall consistency and solidarity in foreign policies. Ultimately, this will lead to a reduced role for BRICS as a whole, potentially resulting in the withdrawal of some members, transforming it into more of a diplomatic and rhetorical forum rather than a platform for specific agendas, and making it more aligned with the interests of the dominant powers within it.

This scenario is not unlikely, at least in the short term. Both the old and new member states of BRICS will work towards achieving and successfully expanding the BRICS vision by enhancing coordination in developmental and political areas, while demonstrating global solidarity. This effort aims to present a practical model of cooperation among countries of the Global South.

Scenario 4: No expansion and maintaining low prioritisation of human rights

This scenario assumes that BRICS will maintain its current composition and will not admit new countries in the medium or long term (over the next decade). It also presumes that the group will continue to maintain its current level of focus on human rights issues and that no significant changes will occur in the prioritisation of policies within each member state. As a result, this will ensure overall consistency in the foreign policy outputs among BRICS countries.

Although the future seems open to all four scenarios, each carrying considerable plausibility, this study leans towards this last scenario over the others. The expansion experience will be subject to evaluation by both new and old member states, especially given that it allowed the addition of five countries at once. There will be cautious observation from other countries interested in joining. These processes will not yield immediate or sudden effects but will take time to establish stable trends upon which BRICS+ can base decisions on admitting additional countries. Moreover, the similarity in human rights records among the newly joined countries suggests that current attention to human rights will likely not progress beyond its present level.

Conclusion

The inclusion of Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Iran, Egypt, and Ethiopia in BRICS has rekindled discussions about the nature of the group, the status of human rights issues, and their future in the group’s agenda. Over the past years, the group has attempted to craft a perspective on human rights that aligns with all its member states, striving to create a shared set of values based on cooperation among Global South countries. This approach rejects the politicisation of human rights and the double standards of the West, emphasising the importance of the right to development and collective rights. It is grounded in the belief of achieving global justice while respecting cultural specificity and the right of peoples to choose their own developmental model.

The study revealed a significant level of cohesion among BRICS member states regarding the role of human rights in policymaking, with these countries—including the democracies—assigning a low priority to human rights on their agendas. Both the old and new BRICS members demonstrated considerable consistency in their approach to human rights issues, both within and outside their member states. This consistency was evident in their statements and voting patterns in international bodies such as the General Assembly, the Security Council, and the Human Rights Council. This alignment has consistently placed these countries in opposition to Western values on human rights, as evidenced by their refusal to condemn human rights violations in Russia, China, or countries with close ties to BRICS members, such as Iran, Belarus, and Syria.

Despite the various potential scenarios regarding BRICS expansion and human rights, the study predicts that the current level of attention to human rights will likely persist without significant development. The group is expected to maintain its current number of member states following the expansion until it assesses the outcomes and impacts of this expansion on the group’s results and policy coherence among its members.

This article is originally written in Arabic for Rowaq Arabi.

[2] Srinivas, Junuguru (2022) Future of the BRICS and Role of Russia and China (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan); Zondi, Siphamandla (2022) The Political Economy of Intra-BRICS Cooperation: Challenges and Prospects (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan).

[3] Xu, Xiujun (2020) (ed.) BRICS Studies: Issues and Theories (New York: Routledge).

[4] The accession of these countries to BRICS was accompanied by a rush from official media outlets and many analysts in these nations to highlight the economic, political, and perhaps geopolitical benefits, with little to no discussion of human rights and democracy. However, those concerned with human rights attempted to bring attention to this overlooked aspect, which this study aimed to weave into a network of potential relationships.

[5] Freire, Maria (2018) ‘Political Dynamics within the BRICS in the Context of Multilayered Global Governance’, in Marina Larianova and John Kirton (eds.) BRICS and Global Governance (New York: Routledge), p. 86.

[6] Mukherjee, Bappaditya (2023) ‘Liberal International Order and the Evolution of BRICS’, in Kumar, Rajan et.al. (eds.) Locating BRICS in the Global Order: Perspectives from the Global South (New York: Routledge), pp. 27-28.

[7] De Conig, Cedric, Thomas Mandrup and Liselotte Odgaard (2014) ‘Conclusion: Coexistence in between World Order and National Interest’, in Cedric De Conig, Thomas Mandrup, and Liselotte Odgaard (eds.) The BRICS and Coexistence: An Alternative Vision of World Order (New York: Routledge), pp. 174-175.

[8] Taylor, Ian (2017) ‘BRICS in Africa and Human Rights’, in Pedro Raposo, David Arase, and Scarlett Cornelissen (eds.) Routledge Handbook of Africa – Asia Relations (New York: Routledge) pp. 294-306.

[9] The use of the ‘coherence’ and ‘consistency’ framework is commonly associated with the study of various topics and issues in both social and natural sciences. However, it is more frequently applied in the field of foreign policy, particularly in the case of the European Union. The EU represents an institution with clear objectives and diverse policy-making structures, making it a subject of study for coherence and consistency on both horizontal and vertical levels: horizontally between the Union’s structures and outputs, and vertically between the member states and the Union’s structures and policies. Nevertheless, it suffers from a lack of clear conceptual definitions, especially regarding the two central concepts and the relationships between them. For more on the application of this framework, its implications, and its applications, please refer to.

Thaler, Philipp (2020) Shaping EU Foreign Policy Towards Russia: Improving Coherence in External Relations (Cheltenham: Edward Edgar Publishing); Koenig, Nicole (2016) EU Security Policy and Crisis Management: A Quest for Coherence (New York: Routledge); Righettini, Maria Stella and Renata Lizzi (2022) ‘How Scholars Break Down “Policy Coherence”: The Impact of Sustainable Development Global Agendas on Academic Literature’, Environmental Policy and Governance 31(2), pp. 98-109.

[10] Koenig, Ibid. p.2.

[11] Thaler, Ibid. pp. 26-27.

[12] The number of commitments resulting from each summit varies significantly. For example, while the 2009 summit produced around 16 commitments, this number reached 130 during the 2015 summit in Russia and increased noticeably to 160 commitments in 2022 during the South African summit.; Kirton, John (2023) ‘The Evolving BRICS’, BRICS Information Centre, 5 July, accessed on 10 March 2024.

[13] BRICS Information Centre (2021) ‘XIII BRICS Summit: New Delhi Declaration’, BRICS Information Centre, 9 September, accessed on 6 March 2024, http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/210909-New-Delhi-Declaration.html.

[14] In the Fortaleza Summit Declaration of 2014, the BRICS countries expressed their ‘deep concern about the ongoing violence and the deteriorating humanitarian situation in Syria’. They also condemned the ‘increasing human rights violations by all parties’ and reiterated their view that ‘there is no military solution to the conflict’. Furthermore, they ‘called on all parties to immediately commit to a full ceasefire and to allow and facilitate immediate, safe, and unhindered access for humanitarian organizations and agencies, in compliance with United Nations Security Council Resolution 2139’. For more information: Afdandilian, Gregory (2023) ‘The Fate of the Wagner Group in Syria, Libya and Sudan’, Arab Center Washington DC, 18 July, accessed on 2 March 2024, http://surl.li/urddm. ; BRICS Information Centre (2014) ‘The 6th BRICS Summit: Fortaleza Declaration’, 15 July, accessed on 7 March 2024, http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/140715-leaders.html.

[15] Druet, Dirk (2023) ‘Wagner Group Poses Fundamental Challenges for the Protection of Civilians by UN Peacekeeping Operations’, Global Observatory, 20 March, accessed on 16 June 2024, http://surl.li/unsac.

[16] BRICS Information Centre (2023) ‘XV BRICS Summit Johannesburg II Declaration’, 23 August, accessed on 6 March 2024, http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/230823-declaration.html, p.2.

[17] Ibid., p. 3.

[18] The BRICS Development Bank is one of the most important economic tools of the group, helping to achieve its objectives. The bank’s establishment was linked to ensuring that developing countries enjoy equal rights to development as developed countries, aiming to shift their position from the periphery to the centre. However, the operational agreement of the bank in 2014, as well as separate statements, did not include any references to commitments related to human rights agreements, except for the Convention on the Rights of the Child. The operational agreement states that ‘the bank shall not impose any restrictions on the procurement of goods and services from any member country with the proceeds of any loan, investment, or other financing provided by the bank’. This provision allows countries to avoid any political or human rights pressure linking financial aid and loans to political reforms or human rights considerations from Western institutions. For more, see: Khambule, Isaac (2023) The BRICS in Africa: Promoting Development (Human Sciences Research Council: South Africa), p. 78.; International Labour Organisation (2022) ‘Employment and just transition to sustainability in the BRICS countries’, 1st BRICS Employment Working Group meeting, led by China, p. 4.; BRICS Information Centre (2014) ‘Agreement on the New Development Bank’, BRICS Information Centre, 14 July, accessed on 6 March 2024. http://www.brics.utoronto.ca/docs/140715-bank.html.

[19] BRICS Information Centre (2023) ‘XV BRICS Summit Johannesburg II Declaration’, Ibid., p. 11.

[20] Hieronymi, Moritz and Danil Karimov (2023) ‘The Right to Development: BRICS’ Understanding of the Human Rights’, International Journal of Law in Changing World 2(2), p.117.

[21] Ibid. p. 118.

[22] World Governments Summit (2024) ‘BRICS & The West: What to Expect in the Next Decade’, Fiker Institute, p. 28, 13 February, accessed 19 August 2024, https://www.worldgovernmentsummit.org/observer/reports/2024/detail/brics–the-west–what-to-expect.

[23] Zondi, Siphamandla (2014) ‘BRICS’ Promise To Decolonize International Development: A Perspective’, Renato das Neves and Tamara de Farias (eds.) VI BRICS Academic Forum, Brazilia: The Institute for Applied Economic Research (Ipea), p. 79.

[24] Käkönen, Jyrki (2019) ‘Global Change: BRICS and the Pluralist World Order’, Third World Thematics: A TWQ Journal 6(4), p. 417.

[25] Liu, Huawen (2022) China’s Path of Human Rights Development (Singapore: Springer Nature), pp. 10-12.

[26] Käkönen, Ibid., p. 418.

[27] Rivers, Lucas (2015) ‘The BRICS and the Global Human Rights Regime: Is An Alternative Norms Regime in Our Future?’, Masters Dissertation, Union College, pp. 581-582.

[28] CIVICUS (2023) ‘CIVICUS: Extremely Poor Civic Space Records of BRICS Countries Undermine its Legitimacy’, CIVICUS, 24 August, accessed on 5 March 2024, http://surl.li/rrswg.

[29] CIVICUS Monitor (2023) ‘People Power Under Attack 2023’, Report, pp. 4-8.

[30] CIVICUS (2023) ‘CIVICUS: Extremely Poor Civic Space Records of BRICS Countries Undermine its Legitimacy.’

[31] CIVICUS Lens (2023) ‘BRICS: The Burgeoning of An International Repressive Alliance?’, CIVICUS Lens, 1 September, accessed on 5 March 2024. http://surl.li/urdfv.

[32] This index assigns countries scores divided into two groups: political freedoms (40 points) and civil liberties (60 points). The assessments are developed with the participation of a large number of advisors, experts, academics, researchers from think tanks, and human rights organisations. In 2024, 132 analysts and forty advisors participated. After studying the situation in various countries during a specified period, they discussed the results of their reports and peer reviews to reach a judgment on the classification of each country. A country is classified as ‘Free’ if it achieves balanced scores in political and civil liberties, with a total exceeding seventy points. In contrast, it is classified as ‘Partly Free’ if it obtains a minimum of thirty-five points.

Freedom House ‘Freedom in the World Research Methodology’, accessed on 15 March 2024, http://surl.li/urvsu.

[33] This index measures economic, political, and civil freedoms through 86 sub-indicators across 12 main areas, including the rule of law, civil society freedom, accountability, freedom of religion, and trade freedom.

Vásquez, Ian et. al (2024) The Human Freedom Index 2023: A Global Measurement of Personal, Civil, and Economic Freedom (Washington: CATO Institute), pp. 3-8.

[34] Thakur, Ramesh (2014) ‘How Representative are BRICS?’, in Thomas Weiss and Adriana Erthal Abdenur (eds.) Special Issue: Emerging Powers and the UN: What Kind of Development Partnership? Third World Quarterly, (London and New York: Routledge), pp. 1800-1801.

[35] Human Rights Watch (2024) World Report 2024, p. 12.

[36] Ibid., p. 569.

[37] Pew Research Centre (2023) Measuring Religion in China, p. 89.

[38] Human Rights Watch, Ibid, p. 99.

[39] Fugairi, Moataz (2023) ‘Will the World Be Better Under the Influence of BRICS?’, Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, 30 August, accessed on 2 March, http://surl.li/rrsou.

[40] China Central Television (CGTN) (2023) ‘Delegation of Globally Renowned Muslim Scholars Visits China’s Xinjiang Region’, China Central Television, 10 January, accessed on 20 January 2024, https://bit.ly/4ajQ0u3.

[41] France 24 (2024) ‘Brazil’s Lula Says No Use Saying “Who is Right” in Ukraine War,’ France 24, 26 February, accessed on 3 March 2024, http://surl.li/rrssm.

[42] Ibid.

[43] VOA (2024) ‘China Describes Navalny Death as “Russia’s Internal Affair”’, VOA, 17 February, accessed on 7 March 2024, http://surl.li/rrstk.

[44] Reuters (2024) ‘Brazil’s Lula says Navalny’s Death Should be Probed Before Accusations’, Reuters, 18 February, accessed 7 March 2024, http://surl.li/rrsuc.

[45] Moscow Times (2024) ‘43 Countries Demand International Probe Into Navalny’s Death’, Moscow Times, 4 March, accessed on 12 March, 2024, http://surl.li/rrsut.

[46] Jütten, Marc and Dorothee Falkenberg (2024) ‘Expansion of BRICS: A Quest for Greater Global Influence?’, European Parliament, p. 5.

[47] Dijkhuizen, Frederieke and Michal Onderco (2019) ‘Sponsorship Behaviour of the BRICS in the United Nations General Assembly’, Third World Quarterly 40(11), p. 10.

[48] Valdai Discussion Club (2023) ‘BRICS Expansion as Non-West Consolidation? The Example of Voting in the UN General Assembly’, 7 September, accessed on 4 March 2024, https://valdaiclub.com/a/highlights/brics-expansion-as-non-west-consolidation/.

[49] It was announced shortly before the last summit that more than 40 countries had expressed interest in joining the group, including Algeria, Bahrain, Kuwait, Morocco, Palestine, and Tunisia, in addition to the group of Arab countries that had already joined since January 2024.; Reuters (2023) ‘What is BRICS, which countries want to join and why?’, Reuters, 21 August, accessed on 28 February 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/what-is-brics-who-are-its-members-2023-08-21/.

[50] Mwamba, The Rt Rev’d Trevor (2023) ‘In the 75th Year Anniversary of The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: a perspective on the emergence of BRICS in a changing world’, Anglicanism, September, accessed on 16 March 2024, https://anglicanism.org/a-reflection-on-brics.

Read this post in: العربية