Introduction: Examining Gender Issues and Political Change in the Contemporary Middle East through an Intersectionality Lens

Citation: Barakat, Kholoud Saber (2022) ‘Introduction: Examining Gender Issues and Political Change in the Contemporary Middle East through an Intersectionality Lens’, Rowaq Arabi 27 (1), pp. 1-5, https://doi.org/10.53833/GNXJ1816

Abstract

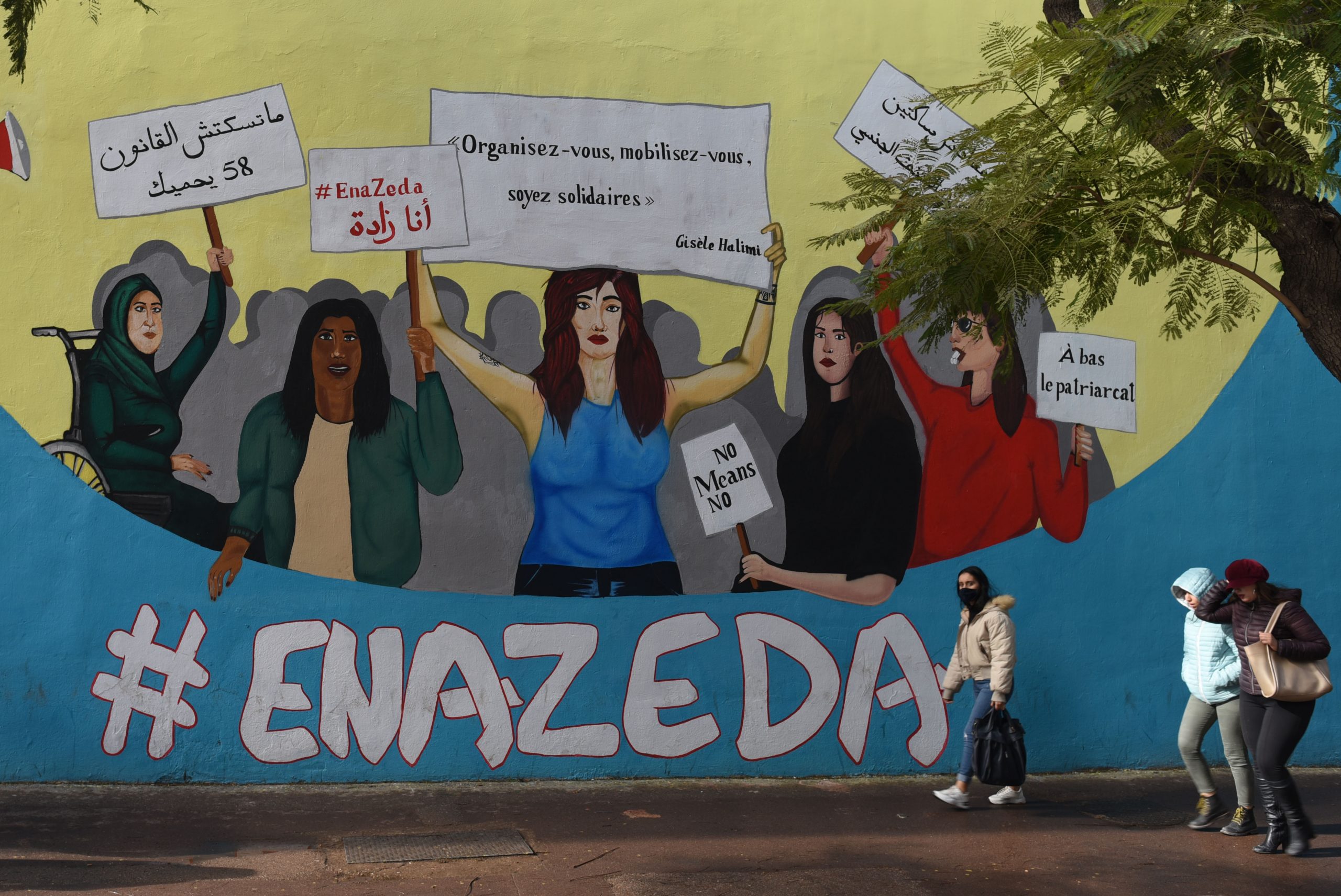

This special Issue of Rowaq Arabi captures the multi-layered changes in the gender politics of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region following the Arab Uprisings of 2011. It employs a critical gender lens to engage with several timely questions concerning the presence of women in the public sphere while examining emerging discourses on gender issues in the region. It presents a general framework that engages with the theoretical understanding of Arab women’s activism and the representation of women’s agency in relation to the Arab Uprisings. In addition, it looks into the Moroccan, Egyptian, and Syrian cases, highlighting the unique and changing underlying dynamics of their political, legal, and social contexts while examining the reflections of these dynamics on women’s mobilisation for equality and rights. A main conclusion reached in the issue is as follows: Despite the complexity and multidimensionality of dynamics determining progress in women’s lived realities following the Arab Uprisings, there is a marked rise in gender consciousness in the region. Furthermore, the research papers in this issue underscore that women’s political and social engagement since the uprisings has already produced new discourses and tools while creating greater opportunities for future change.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region has been established in the social sciences as highly dominated by patriarchal gender roles that rely on restrictive social and religious norms, and are supported by authoritarian political regimes.[1] Nevertheless, beyond the classic dichotomy of Western versus Eastern cultures, some scholars have been emphasising the complexity of gender norms in the MENA region. As these efforts challenge the traditional broad generalisation about gender politics in the Arab-Muslim world, they underline the diversity and complexity across different Arab countries, and in relation to a nexus of generational, economic, political, geographical, and religious factors.[2] Recent research efforts capture how continuing changes in cultural, political, and economic conditions are impacting the structure of gender roles and norms in the region. [3] At the same time, they highlight how the construction of these gender roles and norms are consistently challenged and negotiated by through the everyday behaviour of Arab persons, producing new gender politics that can potentially contest the hemogenic conventional forms. [4]

Moreover, the Arab Uprisings were highlighted as a major turning point in gender politics in the region. Arab women, through their marked engagement in social and political mobilisation during and following the uprisings, succeeded in occupying wider spaces in the public sphere, through which they gained more agency, challenged patriarchal gender norms, breached the silence surrounding entrenched gender-based violence, led public debates on legal and social issues, and pushed the boundaries of conventional femininity. This increased women’s engagement, in addition to socio-economic and political changes that followed the uprisings, has led to changes in gender roles in several Arab countries, raised gender consciousness, and shifted the discourse on several gender and women’s issues. [5]

On the other hand, a marked rise in various forms of gender-based violence perpetrated by individuals or state authorities was also a prominent theme during and following the uprising. This violence was described by several scholars as a counterattack against women’s ability to occupy new spaces and threaten patriarchal gender roles. [6] This theorisation is in line with the hypothesis of ‘Precarious Manhood’ i.e., masculinity being in a ‘precarious state requiring continual social proof and validation’[7] —which links men’s aggression to masculinity being threatened, thus creating a backlash effect that takes the form of social sanctions, including violence against women who challenge gender stereotypes or threaten the gender status quo, with the purpose of maintaining or re-establishing male privilege. [8]

Within this perspective, this special issue of Rowaq Arabi relies on an assumption that since the uprisings of 2011, gender politics in the MENA region have been undergoing a phase of negotiation and restructuring that has produced several key representations on both the discourse and practice levels. We aimed in this edition to capture several key examples of these representations while reflecting upon the extent to which the diverse and multilayered changes in gender politics following the Arab Uprisings may have brought about gains, challenges, and/or losses concerning gender and women’s rights in the region.

Offering a general framework to the major questions we engage with, Reem Awny Abuzaid reflects on Arab women’s engagement in the public sphere during and after the uprisings, through her review of Mounira M. Charrad’s recent book ‘Women Rising: In and Beyond the Arab Spring’. In her review, Abuzaid emphasises how this valuable book presents serious and original perspectives on Arab women’s multiple forms of agency and their activism in mobilising for democracy, social justice, and rights. The book represents a counter-narrative to the mainstream Western academic perspective on Arab women’s presence in the public sphere, and it elevates the underrepresented voices of activists, practitioners, filmmakers, students, artists, and many other women across the region whose experiences have been overlooked. Abuzaid ends her review by underscoring how the book was able to transcend the narrow understanding of Arab women’s political engagement with the actions of protest and mobilisation during the uprisings, as it problematised the perception of 2011 as an unprecedented moment of action while contextualising the mechanisms, meanings, and significance of women’s activism is such complex and restrictive lived realties.

Engaging with women’s issues on legal and institutional levels, Mohamed Drif in his article ‘Gender Policy and Authoritarian Flexibility: The Women’s Quota in Morocco as an Instrument of Regime Support’ tackles the question of how the hybrid nature of Morocco’s political system has resulted in liberal reforms that expanded opportunities for women’s political empowerment in elected institutions without making the regime vulnerable to the uncertainty of genuine democracy. Drif examines several constitutional reforms in Morocco, with particular emphasis upon the women’s quota system and inclusive of those reforms that were initiated in response to the Arab Uprisings. He analyses the extent to which these reforms have contributed to genuine change in favour of women’s empowerment. The article also sheds light on the role of the Moroccan women’s movement in advocating and mobilising on a feminist agenda concerning women’s presence in political institutions. The paper concludes that despite the numerical increase in women elected to the Moroccan House of Representatives, no genuine political empowerment was achieved. On the contrary, in Drif’s estimation, the quota system has become a tool used by the regime to maintain its dominance through the politics of clientelism and party patronage.

On the discourse level, Ricarda Ameling analyses the role of state-controlled media in constructing a new gendered nationalism under the regime of Egyptian president Abdel Fattah al-Sisi. In her article ‘Constructing the National Body through Public Homophobia: A Discourse Analysis of Egyptian Media Coverage of the “Rainbow Flag Case” in 2017’ Ameling highlights how the Egyptian media manufactured a moral panic through their coverage of the Rainbow Flag Case in order to support a self-legitimising gendered nationalism. The article shows how the state-controlled media was systemically part of the state’s aggressive crackdown on the Egyptian LGBTQ+ community, as they portrayed homosexuals as a threat to the Egyptian nation and as part of the West’s attempt to impose a political agenda. The article concluded that media coverage following the Rainbow Flag Case was a conscious tactic used to support the regime’s narrative surrounding its building of a new legitimacy reliant upon gendered nationalist rhetoric. Using this rhetoric, the regime aimed to restore the patriarchal order that was shaken by the Uprising of 2011 and the mobilisation of LGBTQ+ activists that followed. More generally, reinforcing feelings of fear, anxiety, and threat among the Egyptian public was a strategy that portrayed the Sisi regime as the saviour and defender of a moralised national identity, thus contributing to the heightened dominance and stability of the post-2013 authoritarian regime.

Looking particularly into the post-2011 mobilisation against sexual violence in Egypt, Hind Ahmed Zaki in her article ‘The New Feminist Movement Against Sexual Violence in Egypt 2011–2021’ argues that the 2011 Uprising represented a material sphere and grand narrative that allowed for the production of new tools and discourses for a broad feminist movement. She demonstrates how the Uprising allowed for the creation of spaces of action for new and diverse feminist activists who succeeded in proposing an original and more radical feminist agenda. The article captures three phases of the Egyptian feminist movement: the pre-2011 movement, the post-2011 movement, and the most recent movement that followed the suspension of several feminist groups following the 2013 coup. The article ends with an open question regarding the future outcomes of these multiple feminist visions, especially under such a repressive political environment. Yet regardless of these outcomes, Zaki emphatically depicts the 2011 Uprising as a moment that opened new spaces for feminist activism, through which the feminist movement, with its newcomers, was able to put women’s issues on the public agenda in Egypt while bringing in new discourses and tools for mobilisation. Zaki concludes that the new movement represents a new stage of feminist action in Egypt; and therefore, this new feminist movement is one of the most significant and enduring gains of the Egyptian Uprising.

Marina Samir in her article ‘Intertwined Hierarchies: The Intersection of Religion and Gender in the Personal Status Laws of Orthodox Copts in Egypt’ poses another important question concerning the discourse underlying the mobilisation for a unified civil personal status law, which was proposed by feminist activists in Egypt in 2021. Employing an intersectional feminist lens, the article discusses the extent to which such demand reflects consideration of the complex context of Coptic women in Egypt. It engages with this question using a historical review approach, in which Samir presents the main historical milestones in framing the Copt’s personal status litigations. Samir proposes a reading of these milestones while analysing the balance of power between different actors who contributed to the framing of these legislations, including the Egyptian state and the Coptic Orthodox Church. Furthermore, the paper unpacks relevant social hierarchies that determine Coptic women’s position of power, including religious identity and gender. Samir postulates that the dynamic position of Coptic women within the Christian minority compels them to carry the responsibility of representing their religious group while rendering them more vulnerable to higher scrutiny within the Coptic community concerning their behaviour, bodies, and lifestyles. With this understanding, Samir concludes that any proposal for the legal reform of personal status laws that is detached from the rules and lived realities of the Coptic community as a persecuted minority is not a suitable discourse for mobilising Coptic women toward more progressive legislation.

Moving to the Syrian context, Hiba Alhamed discusses the issue of post-2011 women’s activism in exile in her article ‘NGOisation in Exile: Necessity, Professionalisation, and Subjective Space in the Case of Syrian Women Activists in Berlin’. On both individual and organisational levels, Alhamed examines the dynamics of NGOisation as a tool of mobilisation for the Syrian cause, which allow activists to continue their activism and maintain connections with their home county. The article further sheds light on another key aspect of the organisation of women groups in exile, which is the creation of spaces for emotional intimacy and solidarity, in which Syrian women activists can share their personal stories and heavy emotions within a safe environment that provides empathy and support. As the study engages with theoretical perspectives that criticise the tendency towards the NGOisation of social movements as a trend that detaches such movements from their grassroots groups, it emphasises how the contextual complexity of movements in the Middle East following the Arab Uprisings, especially in the case of Syria, positions NGOisation in exile as a gate for keeping the movement alive despite the loss of its popular bases due to distance from the home country. Alhamed ends her study by proposing several important directions for future research, including the examination of coping mechanisms used by Syrian activists to deal with the feeling of guilt, which she highlighted as possible psychological outcomes of practicing activism through professional salaried jobs in exile.

Reading through the articles published in the special edition underlines the complexity and multidimensionality of gender issues in the Arab world. This reading renders unattainable the drawing of an overarching conclusion on whether the Arab Uprisings have led to concrete improvements in women’s circumstances. Nevertheless, the articles shed light on the changes in gender politics in the region. These changes were reflected in the mobilisation of a broader and more diverse population of women and LGBTQ+ activists, the emergence of innovative discourses concerning several gender and women’s issues, the development of new tools of engagement for mobilising on women’s rights and equality, the creation of new spaces that allow women to continue their struggles and activism, and the changing litigations concerning women’s rights. Although it is still premature to determine where these representations will lead, especially taking into consideration the highly repressive political environment throughout the region, it is already evident that these representations offer opportunities for novel, wider, and more radical women and feminist movements that are able to accomplish change despite the high costs.

[1] Alexander, Amy, and Welzel, Christian (2011) ‘Islam and Patriarchy: How Robust is Muslim Support for Patriarchal Values?’, International Review of Sociology, 21(2), pp. 249-276.

[2] Charrad, Mounira (2001) States and Women’s rights: The Making of Postcolonial Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco (California: University of California Press). Rizzo, Helen, Abdel-Latif, Abdel-Hamid, and Meyer, Katherine (2007) ‘The Relationship between Gender Equality and Democracy: A Comparison of Arab Versus Non-Arab Muslim Societies’, Sociology, 41(6), pp. 1151-1170.

[3] Al-Ali, Nadje (2000) Secularism, Gender, and the State: The Egyptian Women’s Movement (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

[4] Kandiyoti, Deniz (1988) ‘Bargaining with Patriarchy’, Gender & Society, 2(3), pp. 274-290.

[5] Al-Ali, Nadje (2012) ‘Gendering the Arab Spring’, Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication, 5(1), pp. 26-31.

Hafez, Sherine (2014) ‘Bodies that Protest: The Girl in the Blue Bra, Sexuality, and State Violence in Revolutionary Egypt’, Signs Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 40(1), pp 20-28.

[6] Kandiyoti, Deniz (2013) ‘Fear and fury: women and post-revolutionary violence’, Open Democracy, 10 January, accessed 20 March 2022, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/5050/fear-and-fury-women-and-post-revolutionary-violence/.

[7] Vandello, Joseph, Bosson, Jennifer, Cohen, Dov, Burnaford, Rochelle, and Weaver, Jonathan (2008) ‘Precarious manhood’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(6), pp. 1325-1339.

[8] Rudman, Laurie, Moss-Racusin, Corinne, Phelan, Julie, and Nauts, Senne (2012) ‘Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1).

Read this post in: العربية