Views: Did the Egyptian Revolution Fail?

Citation: Hassan, Bahey eldin (2021) ‘Did the Egyptian Revolution Fail?’, Rowaq Arabi 26 (1), pp. 5-11. https://doi.org/10.53833/RJMO8598

The uprising of 25 January 2011 was the first significant revolt against the system of governance created in Egypt in the wake of the 23 July 1952 military coup, and the first step toward a new, contemporary system of governance, civilian and democratic. No one can predict how much time or how many more such episodes are needed for the revolution to succeed in Egypt. It ultimately depends on an array of endogenous and external factors. The best Egyptians can do after their failure is to study these factors, in order to understand why they failed while others, like in Tunisia and Sudan, were victorious in the first round of rebellion, at least so far. How should Egyptians change the way they think and act to shorten the road to victory while minimising casualties?

In the years since the uprising, many actors have looked back with an eye toward reassessment, mostly on an individual basis due to the impossibility of holding large-scale gatherings in Egypt where such important issues can be discussed freely. The most striking result of these evaluations is the lack of a broad consensus around any single conclusion. And always in the background lurks a romanticised view of the uprising that aspires to replicate the exact events of 2011. The protests of 20 September 2019, which came in response to an appeal from the contractor Mohamed Ali, are one manifestation of this. These many assessments of course lay blame at the feet of various parties to the events, while more sober-minded analyses are buried in academic publications and seminars. The following lines offer yet another reassessment in an attempt to answer the question asked in the title: Did the Egyptian revolution fail?

Tunisia and Sudan: Why?

Perhaps the best way to approach the question, and one which can spare us dozens of pages, is to start with the two relatively successful models—Tunisia and Sudan—even if their continued success is uncertain. Five interlinked factors enabled the Tunisia uprising of 17 December 2010 to achieve victory and begin a democratic transition, no matter how fragile, on 15 January 2011:

- The Tunisian army is a professional, non-politicised military without political ambition; the minister of defence has been a civilian post since independence from French colonialism.

- The Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT) is a strong trade union of both workers and professionals that has no equivalent in the rest of the Arab world. The UGTT played an important role in the national struggle prior to independence and has occupied a position of esteem for seventy years. It was also able to preserve its independence, and its numerous branches bring together white-collar professionals and blue-collar workers all over Tunisia.

- There was mutual acceptance between forces of the uprising and reformists in the regime of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, and they subsequently cooperated on the democratic transition.

- Early on, the forces of the uprising realised the crucial importance of organising into grassroots committees and thus established the Supreme Authority for the Realisation of the Revolution’s Goals, Political Reform, and Democratisation in 2011. Consisting of liberal academics, rights defenders, and political figures, the authority was backed by reformists in decision-making positions in the transitional authority after 15 January 2011, and it was able to lay important foundations for the democratic transition by issuing several significant pieces of legislation, among them a democratic law regulating civic associations that was consistent with international standards and unleashed civil society and a new election law. An independent commission was also selected to supervise elections, subsequently convening the first free and fair election in the country for the National Constituent Assembly in 2011, tasked with writing the new constitution and assuming the role of the parliament. All of these building blocks came out of the cooperation between reformists and revolutionary forces.

- The Islamist Ennahda movement is a pragmatic, non-dogmatic political movement which, compared to its counterparts in the rest of the Arab world, proved better able to approach politics pragmatically, capably engaging with the reality of Tunisian society and its political and societal evolution and the facts of international politics. It was also adaptable enough to make the decision to exit the government when absolutely necessary, as was the case in 2013.

In Sudan there are also five major factors, albeit different from Tunisia, which enabled the popular uprising to succeed and initiate the process of democratisation:

- The Sudanese military was exhausted—politically even more than militarily—over two decades due to armed domestic conflicts and civil wars that led to large-scale human tragedies, the secession of South Sudan and emerging separatist tendencies in other provinces, and the collapse of the moral status of the military in the eyes of the populace.

- The Sudanese people are the most politicised population in the region. The main parties—conservative ones like the Umma Party and the Unionist Party or modern ideological parties like the Communist Party—were able to maintain their grassroots bases and survive for more than half a century in the face of despotic governments, three military coups, assassinations of a kind not typical for traditional Sudanese society, and three decades of a military Islamist regime.

- Successive Sudanese authoritarians were unable to dismantle Sudanese civil society, particularly its professional syndicates; the latter have always played a vital role in popular uprisings against dictatorships, and their role was decisive in the most recent uprising.

- Sudanese political culture played a vital, historical role that merits the attention of academics. A product of a multi-ethnic, multicultural society that is relatively free of the inward-looking, exclusionary Arab nationalism of societies in Egypt and the Arab Levant, this culture acted as a bulwark against the false nationalist/religious discourse that sought to propagandise and manipulate Sudanese citizens and mobilise them behind bloody ethnic crimes against non-Arab Sudanese in the south and west of the country. In fact, political and civilian Sudanese elites publicly defended South Sudan’s right to self-determination, and civilian political actors in north Sudan joined the political leadership structures of the popular movement to liberate South Sudan during the struggle for secession/southern independence in 2011.

- International, regional, and African actors played a crucial role in securing an orderly and institutional – albeit fragile- transition to democracy by reining in elements of the Military Council that wanted to quell the uprising with the backing of the reactionary Arab regional axis (Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates). The process was secured under US diplomatic aegis in coordination with dynamic Ethiopian mediation. The issues of Sudan’s status as a terrorism sponsor and the International Criminal Court (which is seeking other military leaders in addition to Omar al-Bashir) were both up for negotiation with leaders of the Military Council and this lent indirect support to Ethiopian efforts.

While Ethiopia has never claimed to be a protector of democracy and human rights in the region, as Sudan’s neighbour it nevertheless had a direct interest in preventing internal Sudanese armed conflicts that have sapped all sides from spiralling into a full-scale civil war that would impose severe costs on the immediate region. One drawback to Ethiopia assuming the role of mediator is that it carried little weight with the Military Council in Sudan and therefore was less able to persuade it to compromise. But the United States proactively supported negotiations, though at a distance, by offering the Military Council both carrots (the promise of dropping Sudan from the list of terrorism-sponsoring states) and sticks (the threat of extending the list of ICC defendants to include of the most important member of the council), thereby convincing the council to engage positively with the Ethiopian mediator.

Egypt

None of the ten factors that enabled Tunisia and Sudan to score victories in the first round of their respective uprisings applied to the revolution in Egypt. Egypt has historically lacked a union structure that brings together blue-collar labourers and professionals, and the Egyptian Trade Union Federation (ETUF) was gradually brought under direct police control after the July 1952 coup. Indeed, in 1954 Gamal Abdel Nasser relied on trade unions to mobilise demonstrations against another military faction led by General Mohamed Naguib, then the president of the Revolutionary Command Council, who called on the military to return to the barracks and turn over governance to civilians. As for the principal political Islamist organisation in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood, it was initially opposed to the uprising on 25 January; it only joined in on the fourth day in response to pressure from its youth base, some of whom had defied directives and participated from the outset and later left the organisation. The Muslim Brotherhood only took part in the revolution reluctantly and then under the banner of the political programme it had adopted in 2007, which would establish a different type of authoritarianism.

Certainly, civil society flourished in the decade before the 2011 uprising, as illustrated by the birth of an independent press and media, the increasing number and vitality of activities staged by cultural and artistic platforms, the growing number of independent human rights and women’s rights organisation combined with their increasingly strong ties to youth and their rising effectiveness on the national and international stage. That decade also saw the emergence of non-partisan political groups focused on domestic public affairs. Organising grassroots protests, groups like Kefaya managed to break out of the narrow bounds of action to which legal opposition parties had accommodated themselves; others like the April 6 Youth Movement attempted to attract workers outside the confines of ETUF, coordinating to organise solidarity strikes.

Kefaya, however, had already been eclipsed nearly two years prior to the 2011 revolution, while the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) targeted the April 6 movement and human rights groups for legal, political, and criminal action in the first year of the uprising, seeing them as the bridgehead for international conspiracies against Egypt. Following a nasty smear campaign that went on for months with the collusion of the Brotherhood, in December 2011 military forces raided the offices of several Egyptian and international rights organisations, seizing equipment and files and referring staff to criminal trials. The raid was unprecedented in the more than quarter-century history of Egyptian human rights organisations.

Since Tunisia had never enjoyed much political influence in the Arab region, Saudi Arabia was content to simply host exiled former President Ben Ali. Egypt, however, was a different matter, particularly after the coronation of King Salman bin Abdulaziz and the rise of Crown Prince Mohamed bin Salman, who became the de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia. As the Saudi-Emirati alliance was strengthened, it made countering the Arab Spring its prime objective, particularly in Egypt. Unlike Sudan, Egypt’s African identity is not a key factor in its long-term policies and orientations, celebrated only nominally on certain public occasions. As such, the Saudi-Emirati axis had free, unilateral rein to act in Egypt in the absence of the kind of regional African alliance that later played such a positive role in protecting the uprising in Sudan. Although the African Union froze Egypt’s membership after the July 2013 coup, the suspension was not as long lasting as other international sanctions applied at the same time.

In contrast to Tunisia and Sudan, the Egyptian military is politicised and has substantial political ambitions, having limited the rotation of power to its own leadership ranks since 1952, an uninterrupted fifty-nine years as of the beginning of the uprising. It also enjoys considerable influence, as demonstrated by the currency of its claim to have built the modern Egyptian state—a claim that is easily refuted by a cursory comparison with the reality of the Egyptian state before and after 1952.

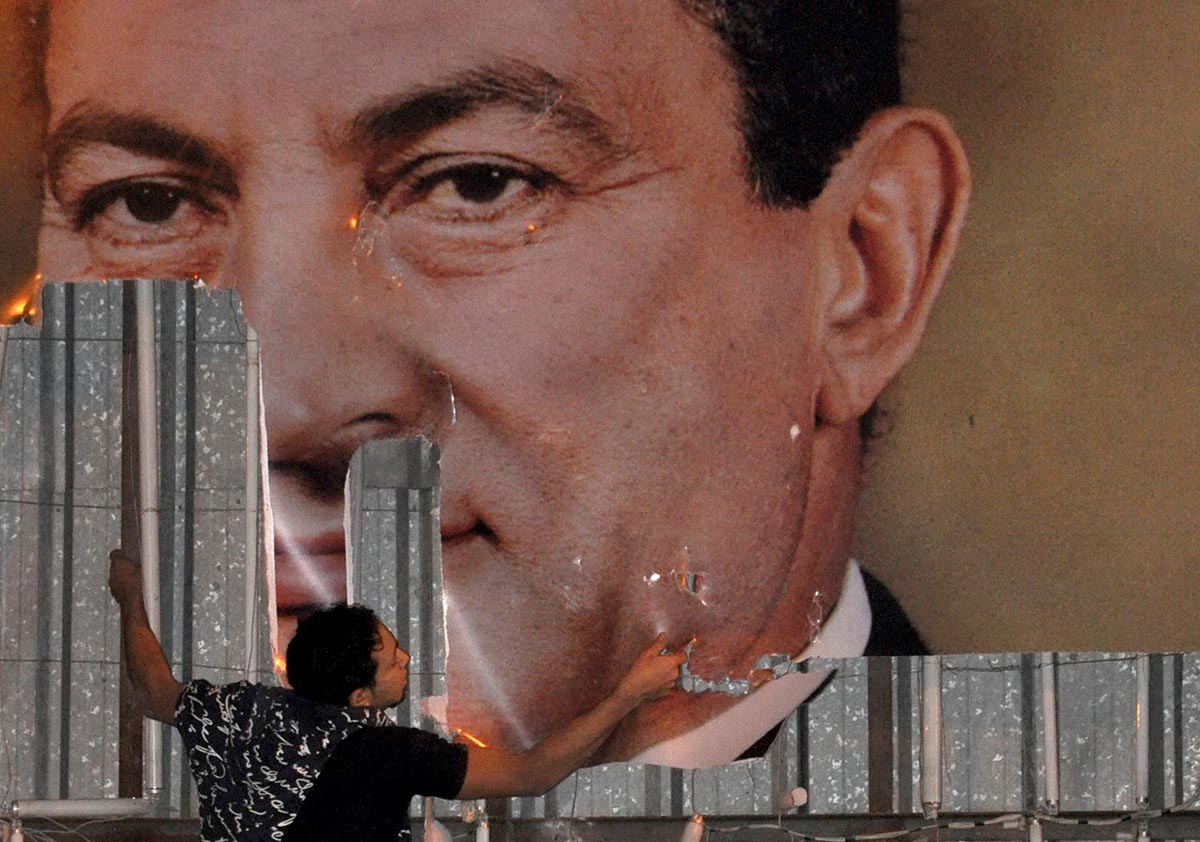

As a deeply politicised entity, the military establishment, led by SCAF, anticipated the uprising before any other security agency, sketching out possible field and political scenarios. Far from seeing the uprising as a threat to itself, the military establishment took it as a fortuitous chance to foreclose the possibility of power passing to a civilian president (Gamal Mubarak) instead of a military successor. The uprising presented a valuable historical opportunity, and not only because this immediate benefit. It also allowed the military to avoid a violent internal clash, with uncertain consequences for the unity of the army, between the military power bases undergirding President Hosni Mubarak’s regime and/or between these and the security factions of the military successor. Thanks to this far-sighted political vision and the consensus around it within SCAF, as well as political cunning, determination, and the mobilisation of all its material, political, and intelligence resources, the military covered half the distance to the seat of power in the eighteen days between the beginning of the uprising on 25 January and Mubarak’s abdication on 11 February, when SCAF assumed de facto control of Egypt with unexpected ease.

At the same time, the revolutionary forces possessed none of the elements of power that the military historically enjoyed or was able to mobilise during the eighteen days. As a result, SCAF was able to mount its non-military offensive against the uprising from a position of strength and on the very next day after the abdication. In this it relied on the dictums of war, the most important of which is to disarm the opponent/uprising of its most powerful weapon: its capacity for large-scale, popular mobilisation in Tahrir Square and other squares across Egypt. By depriving it of its principal weapon, the military could weaken the enemy and dilute its strength before entering into any necessary, direct confrontation. SCAF thus honed in on the long-standing historical divisions between Islamists and secularists, making the same bet that Abdel Nasser had made in the first days of the July 1952 coup to achieve the same objective.

It was not a difficult mission. In the weeks after Mubarak’s ouster, SCAF formed a committee to draft a constitutional declaration to govern the transitional period. The Islamists were the sole opposition party represented in the committee, which they headed, and the constitutional declaration that emerged from that committee reflected the views of the two parties that framed it. Just one month later, the desired division of ranks began to happen on the ground without one bullet fired, when the referendum on the constitutional declaration was held in March 2011. Four months later, Tahrir Square was transformed from the cradle of the uprising into an Islamist million-man march that called the head of SCAF, Mohammed Hussein Tantawi, ‘Amir’. Two years later, the division was christened in blood following the military coup against the Muslim Brotherhood government on 3 July 2013. Nevertheless, in the twenty-seven months before the coup, much blood had already been shed in the streets and squares of Cairo, though Islamists were not the targets. Indeed, they were complicit in the bloodshed, particularly in the Maspero massacre. Occurring only eight months after Mubarak turned over the reins to SCAF, a demonstration comprised largely of Copts was targeted, and twenty-seven people were run over and killed by armoured military vehicles.

The Egyptian uprising lacked an organised leadership with a medium- or long-term strategic vision, a clear programme of action, and an objective, fact-based assessment of allies and opponents. All of this led to costly blunders in the short and medium term and the building of ephemeral alliances based on varying degrees of illusion about each ally. While Mubarak regime reformists were placed on the enemies list, eight years later, a group of leftist, radical, liberal, and Nasserist parties helmed by some of the leaders of the uprising established the Hope Coalition, an alliance between parties led by these very same reformists. Seeing this as a grave threat, the regime of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi derailed the alliance, before it could be announced to the public, by arresting the leadership.

In this historical context, it must be noted that although several prominent secular political figures colluded with the military coup against the Brotherhood government on 3 July 2013 and justified it politically, they came to regret it and critiqued themselves for it. Nevertheless, this reversal did not develop into a response to appeals from secular and Islamist parties to join an alliance with the Brotherhood in the face of a common enemy (al-Sisi) or a reappraisal of the root causes for the political break with the Brotherhood, which began in March 2011 and became more decisive over seminal moments before and after July 2013.

The break is attributable not only to the unprincipled political deals the Muslim Brotherhood made with SCAF (and before that, the Revolutionary Command Council/1952 coup) at the expense of mutual understandings and the objectives of the uprising and its political forces. It can be primarily explained by the yawning gap between bedrock values that shape the parties’ identities and in turn determine their strategic orientations, daily politics, and alliances. There are deep-seated, historical differences between the military and the Brotherhood and bitter experiences of political competition stretching back six decades, punctuated by episodes of brutal repression against Brotherhood leaders and members, including legal murder (execution) and extrajudicial killing. Despite this, nearly sixty years later, the Brotherhood chose, with full awareness, to ally with its killer—the military, brought together by a shared belief in patriarchal values and a common goal of controlling rather than liberating society, though with undeniably different methods and agendas. It was a conscious strategic choice against parties that have never possessed the power to oppress. For the Brotherhood, the problem is that the strategic goal of liberals is the establishment of a modern society on the ashes of the patriarchal one, whose pillars they seek to demolish.

As soon as Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi was elected president in June 2012, the promises made to liberals, enshrined in the Fairmont Declaration a few days before the election, were tossed aside. Although SCAF instituted several hostile legislative and judicial measures on the eve of Morsi’s election, designed to weaken the power of the elected Islamist president and contain the political influence of his organisation, the Brotherhood made a number of crucial concessions to the military, after refusing to concede anything to liberals during the constitution-drafting process, which the Brotherhood oversaw. Most importantly, the Brotherhood gave constitutional cover to military trials of civilians, a first in Egyptian constitutional history. Ironically, several Brotherhood leaders were themselves victims of military courts before the 2011 uprising, when such prosecutions lacked a constitutional basis.

In short, the divide between Islamists and liberals in January 2011 was more about values than mundane political practice. It was between forces that believe in individual liberties and others that do not; forces that prioritise the mechanics of democracy over democratic values, which for liberal forces should take precedence over the mechanics of the ballot box. Perhaps nothing is more expressive of the depth of the gap than the backdrop to the election, and then seating, of the first post-uprising parliament, dubbed the revolutionary parliament. As votes were cast over two months, bloody battles raged in the streets and the flower of Egypt’s youth was systematically cut down just a few metres from the parliament building. Those young people did not see the formation of the parliament as the fulfilment of the goals they fought for, but as the roundabout reconstitution of a regime they discovered had not fallen with Hosni Mubarak’s abdication on 11 February 2011.

This same scene was re-enacted in 2019, peacefully in Algeria, violently in Lebanon, and lethally in Iraq. Having learned this bloody lesson, the uprising leadership in Sudan rejected hastily-convened elections that would reproduce the old regime and insisted on a prolonged, three-year transition before any election.

Read this post in: العربية