Views: Public Sector Workers between Privatisation and State Repression in Egypt

Citation: Nabil, Mohamed (2024) ‘Views: Public Sector Workers between Privatisation and State Repression in Egypt’, Rowaq Arabi 29 (1), pp. 94-109, DOI: 10.53833/UACC3954.

Since its inception, the Egyptian labour movement has overcome many adversities to seize its rights while struggling against the state and political organisations to assert its independence and presence in the public sphere. In turn, it has influenced and been influenced by labour-capital relationships that have prevailed in Egypt for decades. For more than 125 years, these relationships and rivalries have shaped the public sphere in Egypt and influenced political and economic structures. This article analyses a turning point in the relationship between the state and labour: the privatisation programme of the 1990s, which had significant repercussions and ushered in changes that impacted the Egyptian labour movement, labour rights, and the movement’s presence. The article will discuss the relationship between the labour movement and the state and its institutions, examining how the movement developed tactics to confront the political and economic pressures it faced in recent decades. It will also look at the distributional effects of privatisation on workers in general, and the impact of privatisation on development and the living conditions of workers.

The Labour Movement before Privatisation

The labour movement made great strides in both discourse and practice in the first half of the twentieth century. Workers were able to articulate their demands in socioeconomic terms, formulating a discourse distinct from that of political independence, which was monopolised by political elites. On the ground, the movement increased the number of trade unions and workers’ organisations and staged several strikes—for example, the strike at the al-Hawamidiya sugar factory and the strike by Alexandria tram workers in 1919—which the government met with violence. The movement’s struggles brought tangible gains. In September 1937, the Egyptian Labour Movement Organisation was formed by thirty-two unions, and a series of laws were enacted to regulate relations between labour and capital. Law 64 of 1936[1] on work injuries provided for the workers’ right to compensation for job-related injuries. Law 85 of 1942[2] granted workers the right to form unions to represent their interests, preserve their rights, and act to improve their material and social status. Law 86 of 1942,[3] considered supplemental to Law 64 of 1936, required employers to insure against work-related injuries. Law 41 of 1944[4] regulated the contractual relationship between workers and employers in an attempt to codify that relationship into law. Even as labour struggles resulted in these gains, the working class encountered stiff resistance from the bourgeois elites and landowners who controlled the legislature. The trade union law limited the role of unions, allowing them ‘to carry out all union-related tasks exclusive of interference between the servant and his employer or between the worker and the employer’. The labour contract law provided for fifteen days of annual paid leave for monthly salaried workers and just seven days for daily wage workers. In addition, these laws carved out numerous exceptions that were left to the discretion of the executive authority.

By the beginning of the 1950s, the labour movement was highly organised and mobilised. The number of trade unions increased from 210 in 1944 to 500 in 1949,[5] and the working class had expanded to one million workers, in addition to 1.4 million agricultural labourers.[6] At the outset of 1952, the labour movement was preparing for the inaugural conference of the labour federation on 27 January, but the Cairo fire on 26 January and subsequent events prevented the conference from taking place. The Free Officers’ coup on 23 July of the same year marked a new stage in the life of the working class. Seeing in the young officers’ rhetoric a way to undercut the power of the ruling class and its monopoly on wealth and power, labour initially sided with the officers in the hope of achieving political change that would bring them socioeconomic gains.

However, the events of Kafr al-Dawwar[7] demonstrated the new regime’s position on the labour movement early on, and ‘carrot and stick’ politics governed the relationship between the two parties over the next two decades. As the regime stabilised after 1954, it relied on three parallel tracks to reshape the state’s relationship with workers. In the mid-1950s, the state took the lead in the economy, determining the conditions of accumulation and choosing the sectors to which the surplus was directed. The Ministry of Industry was established by Presidential Decree 2 of 1956,[8] and it was followed by several planning and management institutions and structures. Law 20 of 1957,[9] for example, established the Economic Institution, which under the law became the holder of the government’s shares in joint stock companies and the capital of public institutions. These laws, along with Egyptianisation and nationalisation decrees, played a major role in significantly increasing the size of the public sector. The industrial public sector accounted for ninety per cent of the total value added of the industrial sector, and the number of workers in the sector increased from 260,000 in 1952 to more than 577,000 in 1967.[10] This coincided with a set of laws, such as Decree 8 of 1958, which required membership in the National Union—subsequently, the Arab Socialist Union—to run for union offices. Article 162 of the 1959 labour law barred the formation of more than one union for workers in the same industry throughout the country. The goal was to clip the wings of the labour movement, bring it to heel and turn it into a static, non-politicised bloc that could be easily mobilised through the Egyptian Trade Union Federation (ETUF), a new organisation created by the regime to supplant the Labour Federation. At the same time, the state sought to co-opt and integrate workers into the new social coalition with a set of laws in the early 1960s that granted them many economic and social rights. Law 111 of 1961[11] designated twenty-five per cent of net corporate profits to be distributed as income to employees and workers, ten per cent in cash and the remainder in the form of social services and housing. Law 133 of 1961[12] limited the workweek to forty-two hours, while Law 262 of 1962[13] doubled the minimum wage, raising it to twenty-five piasters a day for workers in companies affiliated with public industrial institutions. Workers also had formal representation on corporate boards and immunity from arbitrary dismissal. These terms shaped the social contract between workers and the state for nearly two decades.

At the beginning of the 1970s, the labour movement began to regain part of its vigour. In 1971, workers at the Iron and Steel Company struck demanding higher wages and better working conditions. Scarcely a year later, Shubra al-Khaima workers also went on strike, and in 1975 workers in Helwan occupied the factories and demanded freedom of the press and the dismissal of the prime minister. In the face of this growing labour momentum, the People’s Assembly issued Law 35 of 1976 on trade unions,[14] which expanded the powers of ETUF while maintaining its hierarchical structure. Local union committees formed the base of organisation, and their relationship with the ETUF leadership was mediated by the general unions. The law also designated ETUF as the leader of the Egyptian labour movement, responsible for drafting general policy and developing labour plans and programmes. The law further gave a set of grants and benefits to members of union boards of directors, with the aim of ensuring their loyalty to the ruling authority, which was exactly what happened. ETUF eagerly condemned labour protests and strikes, demonstrating its commitment to state policy.

Workers played a major role in the bread uprising that erupted on 18 and 19 January 1977, following the government’s decision to lift subsidies on some food commodities at the direction of the International Monetary Fund. The government ultimately reversed its decisions, motivated in significant part by strikes and sit-ins. The success of the protests in achieving a large part of workers’ demands encouraged labour to extend those demands beyond the factory walls throughout the 1980s, as workers made persistent attempts to reform unions. This period saw broad labour participation in protests. Railway workers went on strike in 1986, and workers with the Iron and Steel Company in Helwan staged a sit-in in 1989 demanding greater incentive pay and the withdrawal of confidence from the local union committee. Sit-ins rather than strikes dominated in this period, as workers sought to maintain production. Some observers attributed this to the continuation of the culture that prevailed in the Nasser era, whereby workers viewed the public sector as the people’s property and production as part of the struggle.[15]

Labour’s growing politicisation was characteristic of this stage. Workers repeatedly chanted against the government and demanded the dismissal of the prime minister or other ministers. They also challenged the ruling party, attempting to field candidates for parliament. Nor was their activism limited to domestic politics. Workers opposed the regime’s foreign policy as well, rejecting a visit to the factories of the Helwan Iron and Steel Company by then Israeli President Yitzhak Navon; the visit was cancelled.[16] The workers also developed tools to express their opinions and discuss the general situation in Egypt. They issued magazines and newspapers, such as New Dawn, put out by workers at the Delta Iron and Steel Company in the 1970s, and Industrial Workers’ Talk, published by the workers with the Iron and Steel Company in Helwan in the same period. Workers acquired negotiating skills following contact with other political and human rights forces. True, the majority of strikes were ended by the violent intervention of the security services, including the railway workers strike in 1986 and the strike at the Iron and Steel Company in Helwan in 1989, which the security forces broke up with brutal force, using live ammunition and killing worker Abd al-Hayy Mohammed. Nevertheless, workers won their demands, at least partially, after difficult negotiations with state representatives.

But the most prominent feature of that period was workers’ steadfast efforts to assert their independence from state organisational structures, first and foremost ETUF. Strikes and sit-ins were not authorised by the federation, and worker-issued newspapers and magazines were replete with criticism of the role played by ETUF leaders, their constant alignment with the state, their privileging of their personal interests over those of other workers, and their denial of the slogans they themselves championed in 1960s. In fact, when negotiating with the state, workers consistently sought to choose their representatives from among the strike leaders, who spoke on their behalf and expressed their demands to the state apparatus, while ETUF leaders lined up on the side of the state in negotiations. These organisational actions served to promote democratic practices among the labour movement, albeit indirectly and somewhat gradually, as evidenced not too many years later with the beginning of the Mahalla strike in 2006.

Privatisation: Qualities and Forms

Privatisation is defined as the process of transferring economic assets from state ownership, represented by the public sector, to the private sector in its varied forms. This process entails the legal redefinition of property rights and, hence, the ownership of the surplus and the responsibility to dispose of it. The process has economic implications as well, entailing a shift in the conditions of the accumulation and allocation of material and monetary productive assets, as well as social consequences, manifested in changes to the existing social alliance. This makes privatisation a political issue par excellence.[17] Privatisation takes five forms, most famously the sale of public sector assets—in part or in whole—to the private sector. This may be accomplished through a direct sale to private investors, by offering the company on the stock exchange, or via liquidation, though the latter is comparatively rare. In liquidation, the assets of the facility are sold after production has been halted, rather than selling them as an operating facility. The second form of privatisation is a concession, whereby the government grants a private investor the right to exploit a specific asset for a particular period of time. The third form is a leasing contract: the government leases an asset to a private investor for a defined period of time and according to specific conditions. The fourth form is a management contract, which differs slightly from the previous two types. The investor does not assume the capital costs or commercial risks of the project, or bear operational or investment expenses, but is rather responsible for managing the asset based on a set fee schedule. The fifth and final type is a service contract. Similar to a management contract, the private investor performs specific, contracted services, acting as a supporter of the public sector or government by providing a specific service or performing a specific role required by operations.[18]

We can understand the process of privatisation as what Marxist theorist and geographer David Harvey calls a form of accumulation by dispossession.[19] Harvey argues that the acquisition of public property by the private sector—often with the help of the state—is a solution to private capital’s accumulation problems. One of these problems is the acute contradiction between capital’s tendency towards overaccumulation and its capacity to absorb this surplus through consumption or investment, or through what Harvey called spatial fix, of which privatisation is one manifestation, or temporal fix, such as financialization and its applications.

In May and November 1991, following several aborted attempts, Egypt signed an agreement with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, respectively, for the Economic Reform and Structural Adjustment Programme. Privatisation—or the so-called reform of public enterprises—was a key pillar of the programme. Subsequently, a spate of laws was enacted aimed at creating an appropriate legal climate, most importantly Law 203 of 1991 on public business sector companies,[20] which created a public business sector as a bridge to the transfer of public sector institutions and property to the private sector.[21] The law changed the legal nature of public sector enterprises, from public, state-owned property that could only be disposed of by law to a private, state-owned property that could be disposed of by administrative decree.[22] The law also made public sector institutions more independent of the state and gave them greater financial and administrative autonomy in order to incorporate them into holding companies as a prelude to privatisation. In 1992, Law 37 and Law 95 were enacted with the aim of developing the financial sector—banks, credit, and the capital market—to create the administrative and regulatory institutions necessary to proceed with privatisation. In 1993, the Public Assets Management Programme was approved, and Egypt received a grant of $4 million from USAID to implement the privatisation programme, in addition a sum not to exceed $35 million dollars over the life of the project and depending on the availability of funds; USAID also assisted Egypt in the implementation of the programme through institutional development and assistance in the sale of public sector enterprises.[23] This legislation reorganised the public sector into twenty-seven holding companies representing twenty-seven sectors, and comprising 314 companies with assets estimated at LE86 billion and a workforce of more than one million.[24] These companies constituted the core of the privatisation programme.

In order to proceed with privatisation, a set of laws and decree were issued that clarified the procedures to be followed to complete the privatisation of public assets.

Table (1)

| Phase 1: The company to be sold is identified and removed from state control; criteria and controls for the privatisation of the company are proposed. This is undertaken by the Ministerial Committee for Privatisation, which approves the recommendations of the competent minister of investment regarding the value of the company and the assets offered, and then refers its conclusions to the Cabinet for approval. |

| Phase 2: The minister of investment authorises the competent company to proceed with privatisation and to conclude a contract of sale on behalf of the state, which owns the company’s capital pursuant to Presidential Decree 231 of 2004 regulating the Ministry of Investment and Minister of Investment Decree 342 of 2005. |

| Phase 3: The Ministerial Group for Economic Policies, chaired by the minister of finance, approves completion of the sale procedures pursuant to Article 26(bis) of the implementing regulations of Law 203 of 1991, which requires the group’s approval for the completion of the sale of companies to a major investor before the sale is presented to the general assembly of the Holding Company for Trade. |

| Phase 4: The general assembly of the Holding Company for Trade approves the sale pursuant to Law 203/1991 on the public business sector. |

| Phase 5: The details of the sale are presented to the Ministerial Committee for Privatisation and the Cabinet for approval and ratification of the sale. |

| Phase 6: The body authorised to sell the company by the minister of investment (the competent holding company) provides the Assets Department of the Ministry of Investment with a full copy of the sale documents and proof of the transfer of proceeds of the sale of the state-owned asset to the competent account in the Central Bank immediately upon completion of the sale, pursuant to Minister of Investment Decree 342/2005. The proceeds are credited to the state treasury and its account, represented by the Ministry of Finance, after deducting sale costs and expenses, as approved by the seller in accordance with Prime Ministerial Decree 1506 of 2005 on the regulation of the proceeds of the State-Owned Assets Management Programme. |

Source: Memory and Knowledge Studies (2022)[25]

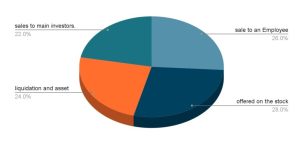

All told, 382 companies in multiple sectors were privatised between 1991 and 2009 by various and diverse means. Revenues from the sale of these companies amounted to LE57.353 billion, sixty-eight per cent of which was earned between 2004 and 2009, when forty-five per cent of the privatisation programme was implemented—the largest part.[26] It is no coincidence that this phase saw the growing political influence of businessmen, on the rise since the turn of the millennium, led by Gamal Mubarak, the youngest son of the then-president. During this period, businessmen headed several ministerial portfolios, while Ahmed Nazif served as the prime minister.

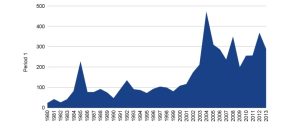

Figure (1)

Privatisation Programme 1991- 2009

Source: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (2008)[27]

The privatisation process in Egypt also coincided with growing state support for the financial and real estate sectors. The financial sector expanded until its assets constituted 78.32 per cent of GDP in 2002, up from just 48.5 per cent in 1990,[28] and by the late 1990s, real estate had replaced agriculture as the third largest non-petroleum investment sector after industry and tourism. Support for the real estate sector was reflected in the policy of public land allocation and credit accommodations given to real estate developers. As for the financial sector, the state bailed out the country’s banks with a cash infusion, in the form of treasury bills worth about 5.5 per cent of GDP in 1990/91, and then exempted them from taxes on these subsidies, the equivalent of about ten percent of GDP by 1996/97.[29] Paradoxically, these subsidies came amid the rise of neoliberal rhetoric in Egypt demanding that the state withdraw from the economy and abandon its social role in order to resolve successive fiscal crises.

Three Forms of Resistance

Seeing privatisation as an attempt to strip them of their social and economic rights, workers consistently opposed privatisation. Their resistance took three forms; sit-ins and strikes, the development of a litigation as a weapon, and attempts to form independent unions to counter the dominance of ETUF.

Strikes and sit-ins were the core practice used by workers to confront ‘economic reform’ policies. Between 1988 and 2008, nearly two million workers took part in 2,623 labour protests.[30] Protests escalated as the privatisation programme proceeded apace, from an average of 118 protests annually from 1998 to 2003 to 614 and 608 protests in 2007 and 2008, respectively. Protests varied in terms of the background of participants, representation, and independence.[31] In 1994, workers with the spinning and weaving company in Kafr al-Dawwar went on strike; some 15,000 of them participated in the sit-in demanding the dismissal of the company head and the overthrow of the union. The sit-in was met with excessive police violence: four workers were killed during attempts to break up the sit-in, and many were subjected to arrest and abuse.[32] The strike at Misr Spinning and Weaving in Mahalla in 2006 marked the beginning of a new stage in the history of the labour movement. The success of the strike led to a qualitative evolution of the labour movement at the level of demands, which went beyond the conventional framework to call for the institution of a minimum monthly wage of LE1,200 for all workers. The protests extended to the city of Mahalla itself. Despite the regime’s suppression of the strike, it had a profound, longer-term impact on the labour movement, as demonstrated in the active role played by labour strikes during the Egyptian revolution and workers’ demands for regime change.

The second method of labour resistance to privatisation was litigation by workers to disrupt or halt privatisation. Aspiring to prove its seriousness to international institutions, the Egyptian regime adopted the slogan of ‘institutional reform’ in the 1970s, and seeking to demonstrate its commitment, the regime had reformed the litigation system and strengthened the role of the Supreme Constitutional Court (SCC) and the administrative courts. In their efforts to stop privatisation, workers relied on two key legal arguments. Firstly, as administrative contracts, privatisation contracts fall within the jurisdiction of the administrative courts. Since these contracts relate to the activity of a public utility, every citizen has the right to file suit to protect them. This was affirmed by the Administrative Court in ruling no. 34248/Judicial Year 65, issued in the case of Tanta Linen and Oils, which stated that Article 33 of the constitution made it the duty of every citizen to preserve and protect public property. Secondly, it was argued that nationalised enterprises could not be liquidated and their legal personhood could not be terminated by the state.[33] Since several companies on the privatisation block had been nationalised in the Nasser era, their privatisation was thus unlawful. Seizing on these claims, workers resisted privatisation by filing lawsuits challenging the contracts of sale of their companies. Changes that had taken place at the level of the superstructure helped to create a space for some institutions to act independently. In turn, some actors were able to oppose the regime without entering into a direct clash that might have ended with their destruction.

Since the mid-1970s, the regime had embraced the term ‘state of institutions’ in an attempt to change the prevailing view of Egypt among international financial institutions as a state that was institutionally hostile to property rights and did not welcome private investment. This turn resulted in the formation of the SCC in 1979, which since its establishment has played a major role the political and economic spheres, albeit with different implications in each field. Politically, the court was a place where human rights and political organisations and political organisations could challenge the regime, while economically the court was aligned with the regime’s neoliberalism. Nevertheless, the establishment of the SCC allowed human rights organisations, political parties, and trade unions to develop legal tools to resist government policies. As workers turned to the courts to challenge regime policies, they tested the regime’s commitment to the institutional reform that it had touted to international institutions.

This labour tactic resulted in a set of historic court judgments. The Administrative Court, in ruling nos. 34517/JY65 and 40848/JY65, issued on 21 September 2011, invalidated the privatisation of Shebin Spinning and Tanta Linen, reasoning that a nationalised asset could not be converted from a public utility to private ownership. In case no. 40510/JY65, the court ruled that the sale contract of the Steam Boiler Company was invalid because it violated the sale procedures set forth in Law 89 of 1998 on tenders and auctions. Ruling no. 11492/JY65, issued in May 2011, invalidated the privatisation of Omar Effendi on the same grounds. All these judgments were issued after the January 2011 revolution.

Figure (2)

Rulings by the Egyptian Supreme Constitutional Court 1980- 2013

Source: The Supreme Constitutional Court[34]

The third form of resistance adopted by the workers was to seek to break the hold of the ETUF, which was loyal to the regime. During the first decade of the twenty-first century, workers sought to form their own independent unions, especially after the promulgation of the unified labour law in 2003, which allowed employers to hire workers on temporary, fixed-term contracts and dismiss them at their discretion when the contract expired. With the deterioration of living standards for both blue- and white-collar workers, civil servants took the initiative to change their conditions. It began with real estate tax collectors, who organised a campaign to demand wage parity with tax officials who worked under the Ministry of Finance. In its drive to decentralise the bureaucracy, the state had turned many tax officials into mere clerks in local administrations, where their wages were much lower than their counterparts affiliated with the central government. On 3 December 2007, some 8,000 real estate tax officials and their families protested for eleven days in front of the Cabinet until their demands were met and the Ministry of Finance agreed to a wage increase of 325 per cent. The success of the strike encouraged the workers to advocate for an independent union, a demand taken up by the strike committee the following year. By December 2008, more than 30,000 of the approximately 50,000 workers employed by local authorities across Egypt had joined the new union, and in April of the following year, the union was recognised by the Ministry of Manpower and Immigration, becoming the first independent union in Egypt in more than half a century.[35] These events spurred teachers and health care technicians to take up the struggle for their own independent unions, which both sectors won. In 2011, the Egyptian Federation of Independent Trade Unions (EFITU) was established, with the support of the Centre for Trade Union and Worker Services, by the Independent Union of Real Estate Tax Workers and the independent unions for health care technicians and teachers. While EFITU played an important role in the following years, it encountered administrative and bureaucratic hurdles to organisational development and was plagued by internal divisions motivated by personal factors.

The Distributional Effects of Privatisation

‘The reform programme did not remove the state from the market or eliminate profligate public subsidies. Its main impact was to concentrate public funds into different hands, and many fewer. The state turned resources away from agriculture and industry and the underlying problems of training and employment. It now subsidised financiers instead of factories, cement kilns instead of bakeries, speculators instead of schools.’ [36]

International financial institutions presented privatisation as a key pillar of their economic reform programmes in Egypt, seeing it as a technical solution to economic crises and a remedy for the authoritarian nature of its political system. In this view, economics is a depoliticised arena whose dysfunctions can be addressed by technical interventions. But this view was not vindicated. Crises continue to periodically ravage the Egyptian economy despite the state’s commitment to privatisation since the 1990s, which had been repeatedly lauded as a success story by these institutions.

For these institutions, success is evaluated based on the material proceeds of the sale of public assets and the speed with which the process is accomplished. Privatisation is measured by the number and size of assets put on offer without regard for the method or trajectory of the process as a whole. Ignored or deliberately omitted from these discussions is the real developmental returns on privatisation. What are the impacts of privatisation on development?

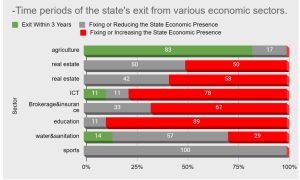

Figure (3)

State Ownership Policy Document- Arab Republic of Egypt

Source: State Information Service (2022)[37]

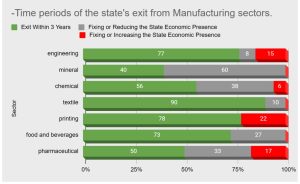

Figure (4)

State Ownership Policy Document- Manufacturing Sector

Source: State Information Service (2022)[38]

This is the question that should be at the heart of discussions of privatisation, if not at the heart of discussions on economic policy in general. The private sector’s contribution to GDP, at current prices, rose from sixty-one per cent in 1989/90 to seventy-two per cent in 2018/19.[39] Capital’s share of GDP increased from sixty-eight per cent in 1995/96 to seventy-seven per cent in 2012/13,[40] while labour’s share fell from thirty-two per cent to twenty-three per cent in the same period. While the public sector employed 69.9 per cent of the workforce in 1995, it employed just 22 per cent by 2017; private sector employment remained steady in the same period, increasing from 30.1 per cent to thirty-two per cent. These figures illustrate the deterioration of workers’ conditions. In particular, the private sector has proven unable to absorb surplus labour, pushing many job seekers into the informal sector, whose share of employment has grown significantly, reaching thirty-six per cent in 2017.[41] The poor quality of jobs available in the informal sector has had implications for labour conditions as well. Health insurance coverage fell from thirty-five per cent in 2010 to twenty-nine per cent in 2017, and in the informal sector is virtually non-existent. The poverty rate among workers increased from eighteen per cent in 2004 to twenty-nine per cent in 2017.[42]

These outcomes make it necessary to question development, especially with a new wave of privatisation underway after the government released the state ownership document in June 2022, which was praised by international financial institutions.[43] Setting aside the seriousness of the government’s desire to move forward, the latest round of privatisation is different from that of the 1990s. The state no longer puts companies up for sale but chooses to exit entire sectors in whole or in part without a full consideration of the implications. The nature of today’s ruling coalition and the latitude for domestic and foreign manoeuvring are completely different than in the 1990s, and the same is true of various actors’ ability to exploit opportunities and adapt to regional and domestic conditions. In addition, the labour movement is in dire straits, poorly organised and subject to greater repression, while the margin of freedom enjoyed by some judicial institutions in the past has vanished. This raises more questions about the coming privatisation wave.

Conclusion

The Egyptian labour movement struggled for decades to attain its political and social rights, encountering state repression and attempts to control it at most junctures. Indeed, this has been a consistent approach of the modern Egyptian state regardless of the change in regimes and their goals and directions. One of labour’s decisive struggles has been against privatisation, which was presented as key to solving Egypt’s economic crisis and a miracle cure for the authoritarian nature of the Egyptian state and the rampant corruption of its bureaucratic apparatus. This view emerged in the context of major political and economic shifts that began in the early 1980s, which resulted in the tenets of neoliberalism becoming universalised and taken as valid for all countries. But the treatment was not successful: the Egyptian economy continued to be buffeted by regular, ever more acute crises, and these solutions did not clear the way for new actors or resolve administrative corruption. In fact, existing problems were exacerbated, and the situation deteriorated further. These policies, especially privatisation, merely served to redistribute wealth upwards while the working class was impoverished.

The latest wave of privatisation comes as the labour movement is at its weakest, after the regime has worked to neuter it and its capacities in recent years and at a time of heightened authoritarianism in Egypt. Experience shows that pushing the state out of the economy only leads to further political and economic deterioration. Over the past decades, privatisation has been accompanied by laws that have curbed the development of organisations and trade unions. The downsizing of the public sector, which represents a solid, organised base for the labour movement, has had adverse consequences for all workers. What Egypt needs to overcome its crisis is not more technical recommendations or superficial policy solutions, but more organised political action that would restore the role and influence of trade unions and labour organisations.

This article is originally written in Arabic for Rowaq Arabi.

[2] Legal Publications (1942) ‘al-Qanun Raqam 85 li-‘Am 1942 bi-Sha’n Niqabat al-‘Ummal’ [Law 85/1942 on Labour Unions], accessed 13 December 2023, https://manshurat.org/file/30869/download?token=js3M_Id7.

[3] Legal Publications (1985) ‘al-Qanun Raqam 86 li-‘Am 1985 bi-Sha’n al-Ta’min al-Ijbari ‘an Hawadith al-‘Amal’ [Law 86/1985 on Compulsory Insurance for Work Accidents], accessed 13 December 2023, https://manshurat.org/file/82383/download?token=tJr77ULs.

[4] Legal Publications (1944) ‘al-Qanun Raqam 41 li-‘Am 1944 al-Khass bi-‘Aqd al-‘Amal al-Fardi [Law 41/1944 on Individual Labour Contracts], accessed 17 December 2023, https://manshurat.org/file/81040/download?token=ONMIvBLt.

[5] Centre for Socialist Studies (2014) ‘al-‘Ummal wa-l-Niqabat: Sultat Ra’s al-Mal wa-Mustaqbal Kifah ‘Ummal Misr min Ajl al-Niqabat’ [Workers and Unions: The Power of Capital and the Future of the Egyptian Workers’ Struggle for Unions].

[6] Duwair, Mohammed (2021) ‘al-Wa‘i al-Muqaddas: al-Haraka al-‘Ummaliya bayn Thawratay 1919–1952’ [Sacred Awareness: The Labour Movement between the Revolutions of 1919 and 1952], in Yehya Fikri (ed.) Maraya 25 [Maraya 25] (Cairo: Maraya Publishing and Distribution).

[7] In 1952, workers at Misr Spinning and Weaving in Kafr al-Dawwar went on strike. Despite their support for the army, their protests were met with extreme violence by the security services. Three people were killed (workers and security personnel) while 28 workers were injured and 528 were arrested. Of these, 29 were prosecuted in a military court, which sentenced two workers to death (Mustafa Khamis and Mohammed al-Baqari), a first in the history of the Egyptian labour movement. The sentence was carried out on 7 September, 21 days after it was handed down.

[8] Legal Publications (1956) ‘Qarar Ra’is al-Jumhuriya Raqam 2 li-‘Am 1956’ [Presidential Decree 2/1956], The Official Gazette 5(bis)(b).

[9] Legal Publications (1952) ‘al-Qanun Raqam 20 li-Sanat 1952 fi Sha’n al-Mu’assasa al-Iqtisadiya’ [Law 20/1952 on the Economic Institution], The Official Gazette 5(bis).

[10] Social Justice Platform (2023) ‘al-Jumhuriya al-Ula: al-Misri fi Suddat al-Hukm: ‘Abd al-Nasir wa-l-Jamahir’ [The First Republic: An Egyptian in the Seat of Government: Abd al-Nasser and the Public].

[11] Legal Publications (1961) ‘al-Qanun Raqam 111 li-Sanat 1961’ [Law 111/1961], The Official Gazette, 1 July 1961.

[12] Legal Publications (1961) ‘al-Qanun Raqam 131 li-‘Am 1961 fi Sha’n Tashghil al-‘Ummal fi al-Mu’assasat al-Sina‘iya’ [Law 131/1961 on the Employment of Workers in Industrial Institutions], The Official Gazette, 18 July 1961.

[13] Legal Publications (1962) ‘al-Qanun Raqam 262 li-‘Am 1962 bi-Sha’n Tahdid al-Hadd al-Adna li-Ujur al-‘Ummal fi al-Sharikat al-Tabi‘a li-l-Mu’assasat al-‘Amma al-Sina‘iya’ [Law 262/1962 on the Minimum Wage for Workers at Companies Subsidiary to Public Industrial Institutions], accessed 5 January 2024, https://manshurat.org/file/72037/download?token=ph-wDeNm.

[14] Legal Publications (1976) ‘al-Qanun Raqam 35 li-Sanat 1976 al-Khass bi-Takwin al-Niqabat al-‘Ummaliya’ [Law 35/1976 on the Formation of Trade Unions], The Official Gazette, 27 May 1976.

[15] Bassyouni, Mustafa (2021) ‘al-‘Ummal wa-Dawlat Yulyu: al-Haraka al-Niqabiya al-Misriya bayn al-Musadara wa-l-Istiqlal’ [Labour and the July State: The Egyptian Trade Union Movement between Confiscation and Independence], in Yehya Fikri (ed.) Maraya 25 [Maraya 25] (Cairo: Maraya Publishing and Distribution).

[16] Al-Ansari, Salah (2007) ‘‘Ummal al-Hadid wa-l-Sulb wa-Rafd Ziyarat Navon’ [Iron and Steel Workers and the Rejection of Navon’s Visit], al-Hiwar al-Mutamaddin, 21 June.

[17] Adly, Amr (2022) ‘Muhakamat Masar al-Khaskhasa fi Misr: Qira’a Naqdiya fi Wajhatay al-Nazar al-Iqtisadiya wa-l-Qanuniya’ [Judging Privatisation in Egypt: A Critical Economic and Legal Reading], Amr Adly (ed.), Memory and Knowledge Studies, p: 6–10.

[18] Kanaan, Rahahla (2017) al-Dawla wa-Iqtisad al-Suq: Qira’at fi Siyasat al-Khaskhasa wa-Tajaribiha al-‘Alamiya wa-l-‘Arabiya [The State and Market Economy: Readings in Privatisation Policies and Global and Arab Experiences] (Doha: Arab Centre for Research and Policy Studies).

[19] Harvey, David (2004) The New Imperialism (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

[20] Legal Publications (1991) ‘al-Qanun Raqam 203 li-‘Am 1991 bi-Sha’n Sharikat Qita‘ al-A‘mal al-‘Amm’ [Law 203/1991 on Public Business Sector Companies], The Official Gazette, 19 June 1991.

[21] Ali, Khaled (2018) ‘Qira’a fi Dafatir al-Khaskhasa 1: Bidayat Siyasat al-Khaskhasa fi Misr’ [A Reading of the Annals of Privatisation 1: The Beginning of Privatisation Policies in Egypt], Legal Agenda, 30 January, accessed 16 February 2024, https://bit.ly/3UqJKL6.

[22] Mubarak, Emad (2022) ‘Muhakamat Masar al-Khaskhasa fi Misr: Qira’a Naqdiya fi Wajhatay al-Nazar al-Iqtisadiya wa-l-Qanuniya’ [Judging Privatisation in Egypt: A Critical Economic and Legal Reading], Amr Adly (ed.), Memory and Knowledge Studies, p: 12–31.

[23] Legal Publications (1994) ‘Qarar Ra’is al-Jumhuriya Raqam 534 li-Sanat 1993 bi-Sha’n al-Muwafaqa ‘ala Minhat Mashru‘ al-Khaskhasa al-Muwaqqa‘a bayn Hukumatay Jumhuriyat Misr al-‘Arabiya wa-l-Wilayat al-Muttahida al-Amrikiya’ [Presidential Decree 534/1993 on the Agreement for a Grant for the Privatisation Project Signed between the Arab Republic of Egypt and the United States], The Official Gazette, 5 May 1994.

[24] Kanaan.

[25] Mubarak.

[26] Khalil, Heba (2011) ‘al-Ganzuri wa-l-Khaskhasa’ [Ganzouri and Privatisation], Egyptian Centre for Economic and Social Rights, 7 December.

[27] Saif, Ibrahim, and Farah Choucair (2008) ‘Egypt’s Privatization Initiative Raises Questions’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2 December, accessed 15 January 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/22479.

[28] The Global Economy (2021) ‘Financial Sector Assets as a Percentage of GDP in Egypt 1990–2002’, accessed 4 March 2024, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Egypt/bank_assets_GDP/.

[29] Mitchell, Timothy (2002) Rule of Experts (Berkeley: University of California Press), p. 279.

[30] Beinin, Joel (2009) ‘Workers’ Protest in Egypt: Neo-Liberalism and Class Struggle in 21st Century’, Social Movement Studies 8 (4), pp. 449–454.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Rushdan, Hassan (1996) ‘Intifadat ‘Ummal Kafr al-Dawwar: Sibtimbar 1994’ [The Uprising of Kafr al-Dawwar Workers: September 1994], Majallat al-Sharara, 1 June.

[33] Ali, Khaled (2018) ‘Qira’a fi Dafatir al-Khaskhasa 3: Turuq al-Dawla li-Ihdar al-Mal al-‘Amm wa-Muwajahatuha’ [A Reading of the Annals of Privatisation 3: State Ways of Squandering Public Funds and Confronting It], Legal Agenda, 30 September, accessed 16 February 2024, https://bit.ly/3vZP4M0.

[34] SCC official website, accessed 17 March 2024, https://bitly.cx/06e.

[35] Beinin, Joel (2012) ‘The Rise of Egypt’s Workers’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 28 June, accessed 21 February 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/2012/06/28/rise-of-egypt-s-workers-pub-48689.

[36] Mitchell, p. 282.

[37] State Information Service (2022) ‘Wathiqat Siyasat Milkiyat al-Dawla’ [Document on State Ownership Policy], 14 June.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Cabinet Information and Decision Support Centre (n.d.) ‘Musahamat al-Qita‘ al-Khass fi al-Natij al-Mahalli al-Ijmali bi-l-As‘ar al-Jariya’ [Private Sector’s Contribution to GDP in Current Prices].

[40] Amer, Mona, Irene Selwannes, and Chahir Zaki (2021) ‘Labour Market Vulnerability and Patterns of Economic Growth: The Case of Egypt’, International Labour Organisation.

[41] Assaad, Ragui, Caroline Krafft, Mohamed Marouani, Sydney Kennedy, Ruby Cheung, and Sarah Wahby (2022) ‘Egypt COVID-19 Country Case Study’, International Labour Organisation.

[42] Amer, Selwannes, and Zaki.

[43] Al-Shorouk (2023) ‘Sunduq al-Naqd al-Dawli Yushid bi-Wathiqat Siyasat Milkiyat al-Dawla’ [IMF Praises State Ownership Policy Document], 10 January, accessed 7 October 2023, https://bitly.cx/B5ZG.

Read this post in: العربية