Views: Understanding Risks and Investing in Opportunities while Defending Human Rights in the Time of COVID-19

In the time of COVID-19, the situation in the Arab region and the rest of the world – aside from a few exceptions – continues to deteriorate, albeit at a faster pace. Although it is too early to reach conclusions about what the world will look like when the current crisis recedes, it is likely that the economic repercussions of the pandemic- rather than the pandemic itself- will be decisive in shaping global and national circumstances.

Serious analyses vary greatly in their expectations, and center on three possible scenarios. The scenarios are not necessarily exclusive of each other; one scenario may intersect with another within the same region; and any developments (positive or negative) on a national, regional, or global level are influenced by an array of factors. However, the scenarios are presented in this paper in isolation from each other for the purpose of facilitating discussion and contemplation of the challenges posed by a crisis unprecedented in modern history.

The first scenario is the acceleration of the pre-pandemic status quo: further depreciation of the international order’s institutions and its effectiveness, and an even greater rise in populism and authoritarianism in the Global North and Global South.

The second scenario centers on direct and indirect repercussions of the pandemic – events that would not occur if not for the pandemic. The collapse of the United Nations and European Union systems would be one potential pandemic-specific outcome. Other ramifications include the collapse of some states due to unorganized civil disobedience and the spread of panic amongst the populace. This unrest and panic would be attributable to the public’s lack of trust in the credibility of government information, the government’s mismanagement of state and healthcare systems, and the government’s inability to provide for basic needs and services in the face of the pandemic, leading to a collapse in the rule of law. The pandemic may also lead to mass starvation in some African and Arab states witnessing armed conflicts.

The third scenario is an awakening and “return of consciousness” through a better understanding of humanity’s collective responsibility for its future, a process of “re-globalization,”[1] reinforcing the international system and its institutions, and a greater commitment to climate change. There would be a reclamation of the significance of government spending on health (including the prevention of future pandemics) and social benefits, along with a realization that even some democratic systems need to be reformed in order ensure public spending is aligned with societal priorities.

Under these circumstances, autocratic governments would be challenged and held accountable for their incompetent handling of the pandemic and their deeply-rooted policies that led to avoidable health and economic catastrophes. Greater focus would be directed toward combating institutional corruption, protecting freedom of information, and reinforcing institutions of accountability (parliaments, judiciaries, political parties, media, syndicates, and civil society organizations). Public opinion would further realize the centrality of democracy and human rights on an individual and collective basis.

Implications for Independent Human Rights Organizations in the Region

Human rights organizations in the Arab region should work with their partners on the global, regional, and local levels to promote the third scenario, prevent the first one, and avoid slipping into the second. To do so, organizations should dynamically follow and analyze global and regional developments and reach sound conclusions in a timely manner; reinforcing their abilities to grasp ongoing transformations amidst a politically turbulent context.

At the same time, it is essential to the management of human rights organizations to maintain the highest degree of caution and wisdom on the institutional and personal levels. More than ever, management must combine flexibility, to maneuver around potential risks; and dynamism, to capitalize upon all potential opportunities to reinforce human rights and the conditions to defend them. This will require reinforcing the human rights aspect in potential resolutions to armed conflicts and in reform initiatives in autocratic states. This may require Arab human rights organizations to revise the priorities and structures of some of their programs, and reconsider how they seek to accomplish their goals.

In order to understand the practical implications of COVID-19 on the work of Arab human rights organizations, it is important to uncover the possible trajectories of these scenarios in the context of the Arab region, particularly, the scenarios directly or indirectly induced by COVID-19. In other words, what forms would the second and third scenarios assume?

Opportunities and Risks in Contexts of Probable Horizons of Development in the Region

The second scenario: Mass starvation further ravages Yemen. The scope and intensity of civil conflict in Libya increases. Yemen and/or Libya could fragment. The state of Lebanon collapses and faces bankruptcy. Iraq collapses under the weight of the persistent failure to form (or agree upon) a government, along with plummeting oil prices, rampant corruption, and the growing authority of militias aligned with other states (forty-one of sixty-seven militias are loyal to Iran).

In Syria, the consolidation of foreign military presence and the state’s fragmentation is a reality that will turn the state into several statelets. Sudan faces a military coup (perhaps with a civilian or regional Arab facade) or an open conflict between the military and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), and the renewal of regional civil conflicts along with a growing economic crisis, depreciating standard of living, and the start of a “hunger uprising.” In Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Algeria, and Bahrain, authoritarianism would consolidate. In Palestine, the West Bank would be annexed by Israel, and the Palestinian Authority and Hamas authority would collapse.

The third scenario: There are five important developments underway in the Arab region attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic that could result in the third scenario for the Arab region. In this scenario, there would be a significant reconfiguration of the relationship between the rulers and ruled, which would ultimately lead to substantial gains for human rights and democracy.

The first – and most important – regional development is the qualitative weakening of the five counter-revolutionary forces in the Arab region: Saudi Arabia, UAE, Russia, Iran and Egypt. With the exception of Egypt, the collapse of oil prices has unprecedentedly impacted these states.

The collapse of oil prices has compelled Saudi Arabia and the UAE to turn to credit from international lenders at a high interest rate. With the price of oil standing at twenty USD per barrel, the UAE and Saudi Arabia need prices to increase to sixty-five USD and ninety-one USD respectively to achieve fiscal balance. The repercussions are more severe for Saudi Arabia due to the halting of religious tourism and the impeding of the Crown Prince’s ambitious economic plans to diversify the economy and abandon the welfare state, which traditionally supported free health and education services along with lucrative government jobs. In fact, a cost of living subsidy by the government has been scrapped and VAT has increased threefold.

Additionally, Saudi Arabia is witnessing an escalation of conflict within the royal family amidst suspicions of a coup that was aborted on the eve of the pandemic. Saudi Arabia will undoubtedly be forced to cut down on its immense spending on arms (which made it the fifth largest spender on armaments worldwide), which will likely lead to a significant weakening of its political leverage in the international community and its institutions.

In Russia, oil revenues accounted for thirty-five per cent of the state’s budget last year. While the price for Russian oil fell from forty-six USD to ten USD, exports are expected to fall by forty per cent this year, leading to a forty billion USD deficit. As a result of disruptions posed by COVID-19, Russia lost four trillion rubles, compelling it to borrow from its reserve fund. However, Deutsche Bank stated that the fund cannot cover the deficit for more than two years given a fifteen USD per barrel price. These economic troubles were reflected in a significant decline in Putin’s popularity, perhaps jeopardizing his plans to amend the constitution to run for presidency in 2024.

In Iran, the crash in oil prices has led the state – for the first time in sixty years- to request a loan from the IMF. Iran suffers on three fronts, the first two being the acute effect of American sanctions combined with the immense spread of COVID-19, making Iran the third most affected country after China and Italy. On the third front, Iran has been weakened by the 3 January 2020 assassination of General Qasem Soleimani (Iran’s field coordinator for its alliances in the region) and the inability of Soleimani’s replacement to fill his place.

Egypt is affected by the inability of Saudi Arabia and UAE to financially assist it as the two states have done since the coup in 2013. Nothing reflects the extent to which the oil price collapse is afflicting the counterrevolutionary axis more than economic experts’ conclusion (a conclusion arrived at before the collapse), which stated that the “Arab world’s giant ATM is running out of cash.”[2]

The second development concerns how the pandemic, and the unprecedented economic and health crises arising from it, has put the rulers and the peoples of the Arab region face to face with each other, in a manner that will test the capabilities of both and expose their weaknesses. A recent report from the World Bank states that “The MENA region is particularly vulnerable. MENA scores second-lowest among all regions in the overall Global Health Security Index, while ranking last in both ‘epidemiology workforce’ and ‘emergency preparedness and response planning.’”[3]

Some analysts, in this context, predict a third wave of the Arab Spring,[4] specifically concerning the inability of Arab governments to manage the crisis and the inability of their economic infrastructures to absorb the shocks of the pandemic, rendering the majority of their citizens vulnerable to catastrophic consequences. However, this entails a degree of optimism especially in light of three factors: first, the failure of the first wave of the Arab Spring (with the relative exception of Tunisia) to remove the ruling elites or to ally with the reformists among those elites; second, the systematic destruction of the leadership of the first wave carried out by the counterrevolutionary forces over the years; and third, the inability of the second wave of the Arab Spring to produce leadership (with the exception of Sudan).

Accordingly, we cannot exclude a scenario where chaotic social and economic upheavals take place, which are unable to be contained or managed by the ruling regimes. These upheavals would be driven by the mismanagement of the pandemic, food shortages, millions of job losses without compensation from the government, as well as the peoples’ chronic lack of trust in their rulers’ credibility, integrity, and competence. In the absence of any alternative economic and political plans by some Arab governments in non-oil Arab states, the situation could lead to what the International Committee for the Red Cross has called a “political and social earthquake” with effects that would last for many years. In this context, several considerations present themselves:

- The effect of the collapse in oil prices on millions of Egyptian, Syrian, Palestinian, and Lebanese expatriates and their remittances from Gulf countries, considering that some have already returned to their homes after the pandemic.

- The effect of unemployment in the Arab region, where the youth unemployment rate is already double the global average.

- The effect of 8.3 million people joining the tens of millions living in poverty in the Arab region. The United Nations expects the total number of people living in poverty in the Arab region to reach 101.4 million.

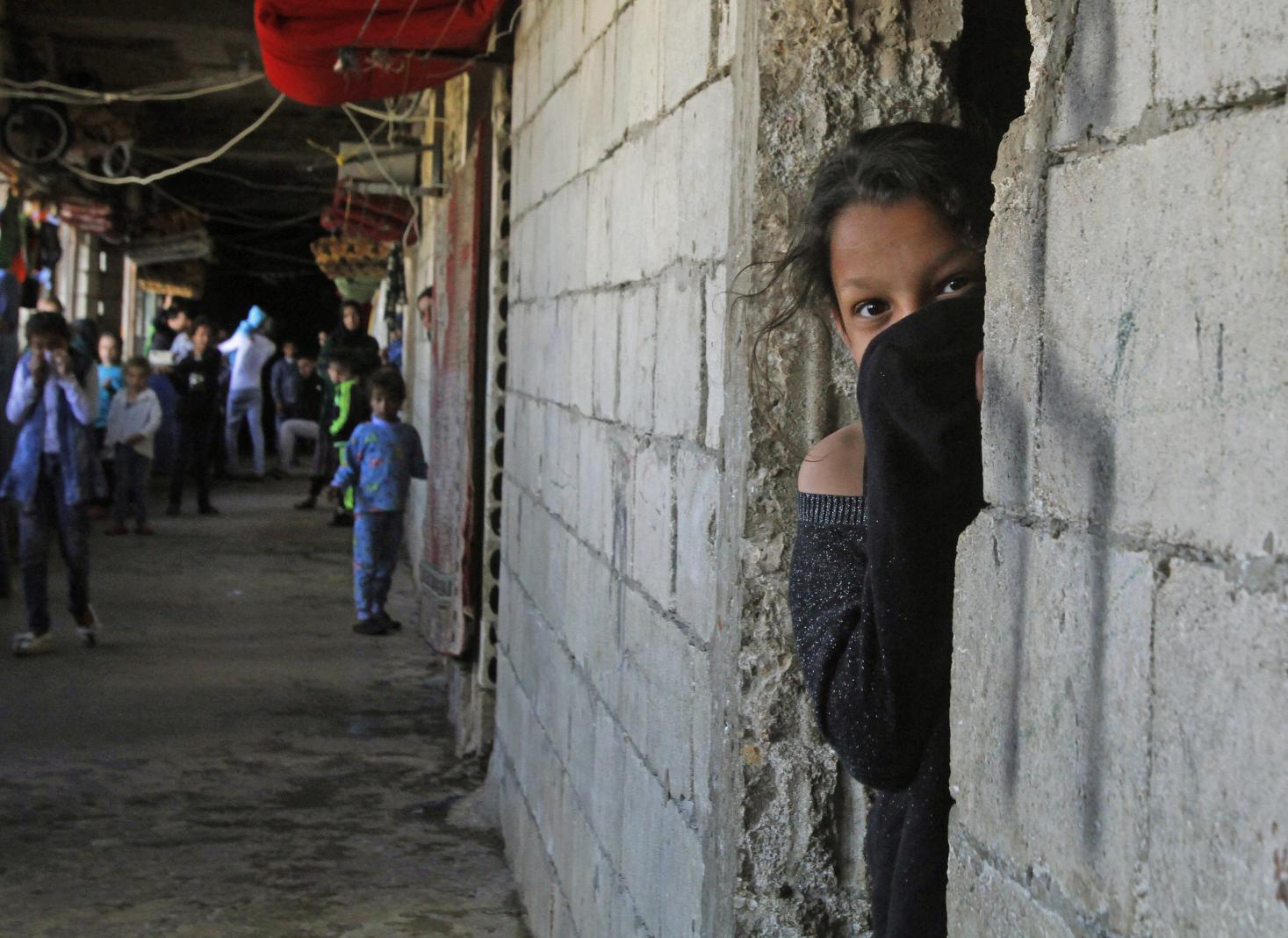

- The effect of the pandemic on twelve million refugees and internally displaced people (the largest number in the world).

- The effect of how ISIS has decided to capitalize on the pandemic, or what the group calls “the crusaders worst nightmare” to reinforce its activities as some indicators point in Syria, Iraq, and Egypt.

The third development is a subtle rise of secularism in Arab societies and the receding of political Islam. The whole world, including those on the more religious side, awaits a scientific solution, not a divine one. For the first time in history, mosques across the region are shutting down without a proportionate reaction.

The fourth development concerns the reality of the human rights struggle across the Arab region. The obvious truth – obscured by a tendency to accommodate authoritarianism – has finally been vindicated: there cannot be progress on social and economic rights (including rights to health and social security) without a minimum guarantee of civil and political freedoms. Civil and political freedoms – exercised through a parliament elected according to international standards, free media and civil society, and independent political parties and syndicates – guarantee societal oversight on government spending and enable civilians and social organizations to influence governmental policies and decisions.

It is important in this context to observe the developments in Tunisia and Morocco since the pandemic began, despite the substantial difference between the political systems of both states. While Tunisia is a democracy and Morocco is an authoritarian state; nevertheless, Morocco’s authoritarianism is founded on a restricted political plurality. This type of plurality distinguishes Morocco from other forms of authoritarianism, such as that found in Algeria or Egypt.

In Tunisia and Morocco, the pandemic was approached in line with the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO). The role of state bureaucracy in both countries was visible while civil society succeeded in stopping governments from using the pandemic as a pretext to curtail freedom of information. In Morocco, the relative degree of freedom halted legislation that targeted social protest movements, which in turn led to a major crisis within the two main parties in the government and may result in the resignation of the minister of justice, despite his appointment by the king.

The fifth development is the division among some of the actors of the counterrevolutionary axis, which could open the door for new opportunities to democratic forces. This is specifically growing visible in Syria and Iraq, as will be explained later.

Opportunities and Risks to Human Rights Work in Arab States in the Time of COVID-19

Yemen

The war-torn country is likely to see the persistence of the fragile unilateral ceasefire, given Saudi Arabia’s recognition it cannot go on with the war, and the victory of the Houthis alongside the sacrificing of the Hadi government. However, this does not mean that other factions will surrender to the Houthis. Local armed conflicts will persist with their own agendas across Yemen, so will attacks by ISIS and al-Qaeda, and a formal separation between North and South Yemen will be in effect. The fragmentation of Yemen carries many regional and international risks, which may lead to political and economic deals capable of absorbing the ambitions of the different factions in Yemen within a federal state, likely with the South going its own way.

Libya

There is as an opportunity in Libya for the resumption of the reconciliation process, which was halted in April 2019. The start of the long march towards rebuilding the state could take place in the context of the weakening of the forces under Libyan National Army commander Khalifa Haftar. Haftar has suffered several defeats, as well as defections among his forces and allied tribes in the east. His regional and international partners are unable to back him due to the pandemic and the collapse of oil prices.

Syria

A new chapter may start in Syria due to the escalation of conflict within the counterrevolutionary axis (Assad, Russia, Iran) and there are indications of a possible agreement between the United States and Russia on a future for Syria without Iran or even Assad. The conflict between Assad and his rivals within the regime is now public, as well as the conflict between him and Putin a year before presidential elections, with Moscow insinuating that it has alternatives to replace Assad. The contention revolves around the future of Syria politically, economically, and militarily; with the division of the reconstruction cake and the size of Iran’s role in Syria being primary issues. The friction is further exacerbated by Moscow’s persistence regarding the necessity of developing and professionalizing Syria’s military, curbing corruption, and opening up to non-armed opposition.

Additionally, Russia is coordinating with Turkey on the situation in northern Syria, while the United States and Israel are concerned with forcing Iran to withdraw from Syria. Meanwhile, Hezbollah is tied up with the uprising in Lebanon (which risks bankruptcy), and ISIS’ resumption of attacks. All this represents an opportunity to walk the long road toward the inclusion of the non-armed reformist opposition and civil society.

Iraq

The weakening of Iran has also been reflected in Iraq, including on its most prominent Shiaa militias, which had been politically and militarily directed by General Qasem Soleimani. The sectarian political parties affiliated to those Shiaa militias had the most to lose from the popular uprising in Baghdad (even in major Shiaa cities) in addition to their loss from Shiaa spiritual leader Ali al-Sistani’s criticism of them. This has led to a fragile consensus on nominating a prime minister relatively independent from Iran and its affiliated parties. While these parties did not object to the nomination of the prime minister, they do possess the power to make him fail.

Although the prime minister does not have the support of the uprising, Mustafa

al-Kadhimi’s initiative on his first day as prime minister included declarations and decisions that respond well to some of the uprising’s most important demands, and this is a positive step. He committed to holding general elections within a year, to immediately releasing all detainees, and to holding those who repressed the uprising accountable. He also announced he will open the file of those kidnapped by militias (around 12,000 abductees) and appoint ministers of interior and defense independent of the militias. Finally, he committed to reappointing one of the most popular military figures to an important post after he had been previously overthrown by militias.

In any case, the situation in Iraq represents a significant opportunity to further democracy and human rights. There seems to be a positive response to one of the uprising’s most prominent demands, that is, to organize elections within a year. This is a seismic change in a state controlled by one of the strongest sectarian powers that opposes democracy and human rights in the region, especially considering the impressively dynamic performance of the uprising, which managed to persist even during the pandemic. This was the only uprising of the second wave of the Arab Spring that succeeded in forming coordination committees, made up of sixteen committees across nine Iraqi governorates.

The fact of the matter is that the ascension of Mustafa al-Kadhimi wouldn’t have been possible if not for the significant shift that took place within the balance of powers, including the dynamism of the uprising [5] and the increasing weakening of Iran (the de facto ruler of Iraq since the American withdrawal in 2011).

Palestine

The “deal of the century” will likely pass with little resistance from the international community, the Arab states, and Palestinian authorities in the West Bank and Gaza. But the political and moral legitimacy of the Palestinian authority, especially in Ramallah, will quickly disappear given the economic crisis, rampant corruption, diminishing public trust, and evolution of internal conflicts into wars of succession. In addition to the likelihood of Mahmoud Abbas’s imminent death, the absence of an alternative institutional path to naming a new president constitutes a challenge. The legislative council has been dissolved, the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) is frozen, and Abbas hasn’t named a successor (he has in fact moved to reinforce his control and marginalize rising officials).[6] This could lead Israel to impose a friendly president (such as Mohammed Dahlan) as Mahmoud Abbas’s successor in coordination with the UAE and Egypt.

This is taking place alongside two important developments. The first is the erosion of the constituents of the two-state solution and even among the Palestinian public (a recent poll suggested 37 per cent Palestinians prefer a binational one-state solution compared to 39 per cent preferring a two-state solution).[7] The second development is the rise of the Arab coalition to becoming the third largest bloc in the Israeli parliament, making it a more influential player than the labor party that founded the Israeli state.

These developments open the door to two possible scenarios for the Palestinian struggle and the role of civil society. The first scenario would be a struggle to carry out a radical political reform process of the Palestinian Authority (PA) and PLO. The second would be a joint democratic struggle for justice and against apartheid in the two-state solution, with a new transnational Palestinian leadership. These developments may require human rights organizations in the Arab region to moderate a dialogue with Arab organizations in Israel and Palestinian organizations in the West Bank Gaza, including the Civil Organizations Network, on these issues.

Tunisia and Morocco

The increased trust of public opinion in the state’s bureaucracy and the depreciating public support for Islamists could lead Morocco to form a new ministerial coalition including the Justice and Development party – but without the party’s chairmanship – after the pandemic. Additionally, there is both risk and opportunity represented in the severity of the economic crisis in both countries and the rise of new social movements.

Algeria

The recently-elected president, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, is dealing with the pandemic as an opportunity to reinforce his authority and rearrange the balance of power in his favor in preparation for the post-pandemic phase. He has moved to contain his rivals in the military, intelligence, and internal security through firings and new appointments and arrested a number of Hirak leaders, mobilizing the judiciary against them in the absence of street mobilization. News websites reflecting the points of view of the Hirak were blocked. President Tebboune amended the penal code under the pretext of protecting the state from what he calls “fake democracy” and is preparing a constitution that does not adopt the most important demands of the Hirak.

Additionally, President Tebboune launched an unprovoked political campaign against France warning against meddling in Algerian affairs, which suggests that he’s preparing to clash with the Hirak. At the same time, oil prices are plummeting and an economic crisis is looming (97 per cent of oil revenue -the only product Algeria exports- is spent on importing the state’s needs). For the Algerian budget to balance, the oil price must rise from twenty USD to ninety USD.[8]

Egypt

President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi is exploiting the pandemic as an opportunity to reinforce his individualistic autocratic rule in preparation for popular protests against the anticipated qualitative deterioration of the standard of living and economic situation in the country. Egypt suffers from the pressure of its obligation to pay its loans (109 billion USD, 6.18 billion of which are owed this year as installments and servicing). This pressure is amplified by the catastrophic decline in income from tourism and from the Suez Canal and remittances, as well as a drop in foreign investment. In May 2020, Sisi was compelled to request a new loan from the IMF for 8.2 billion USD and then sought an additional nine billion USD as loans from the IMF and other institutions. Egypt is facing this crisis while its traditional saviors in the Gulf are unable to promise help. An expert stated that Egypt risks going from “too big to fail to too costly to save.”[9]

President Sisi has amended the emergency law and begun adding secular opposition figures to terror lists. He has not stopped arrests, disappearances, and torture during the pandemic. With increased international pressure to release prisoners in order to avoid overcrowding, he released four thousand inmates charged with criminal activities and none with a political charge. Sisi is aware that fighting the pandemic would put civilians, not military men, once again in the spotlight of saving the state and citizens. Therefore, on a weekly basis he ensures to deceptively present the military, not civilian medical workers, as the shield from the pandemic.

Another objective of these weekly messages for President Sisi is to reinforce his relationship with the military under the current dire situation, given his awareness that the only possible alternative to him is either from the military or from the Mubarak regime, or someone both factions would support. It is obvious, however, that with the spread of the pandemic in May and the inability of the fragile health system to control it, Sisi has stopped addressing the issue with public opinion, leaving it to civilian officials such as the prime minister and the health minister.

[1] The term “re-globalization” is coined by King Abdullah II bin Al-Hussein of Jordan (2020), ‘It’s time to return to globalization. But this time let’s do it right’ The Washington Post, April 27, accessed 22 June 2020, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/its-time-to-return-to-globalization-but-this-time-lets-do-it-right/2020/04/27/b5e8b442-88b4-11ea-8ac1-bfb250876b7a_story.html.

[2] Rosenberg, David (2020) ‘Arab Oil Money Is Running Out, and Chaos Will Likely Follow,’ Haaretz February 12, accessed 22 June 2020, https://www.haaretz.com/world-news/.premium-arab-oil-money-is-running-out-and-chaos-will- likely-follow-1.8511319.

[3] World Bank (2020) ‘How Transparency Can Help the Middle East and North Africa,’ World Bank Group, April, accessed 22 June 2020, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/33475/9781464815614.pdf

[4] For example, see Wehrey, Fredric (2020), ‘Will the Virus Trigger a Second Arab Spring?,’ The New York Times, April 6, accessed on June 22, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/opinion/middleeast-coronavirus.html.; and Miller, Andrew (2020) ‘COVID-19 and the Arab World’s Looming Economic Crisis,’ March 24, accessed June 22, https://pomed.org/covid-19-and-the-arab-worlds-looming-economic-crisis/.

[5] Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies, (2020) ‘TashkilHokoumat al-Kādhemi fi al-ʿiraq: TahawolFiʿliammTaswiyaʿābera’ [Forming al-Kadhemi’s Government in Iraq, a Real Transformation or a Casual Settlement], Al-Modon, May 13, accessed June 22, https://www.almodon.com/arabworld/2020/5/13/تشكيل–حكومة–الكاظمي–في–العراق–تحول–فعلي–أم–تسوية–عابرة

[6] al-Omari, Ghaith and Ehud Yaari (2020) ‘Palestinian Politics After Abbas, Policy Note’, The Washington Institute.

[7] Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research https://www.pcpsr.org/en/node/799/.

[8] Karam, Sohail, and Abeer Abu Omar (2020) ‘Economic Reckoning Is Coming for Algeria,’ Bloomberg, April 20, accessed June 22, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-20/economic-reckoning-is-coming-for-arab-world-s-last-debt-recluse.

[9] Miller, “Covid-19 and the Arab World”

Read this post in: العربية